In this first 2021 episode of the Breaking Smart podcast, I want to talk about something that’s been on my mind a lot lately that I call anti-network effects.

1/ As I am recording this, governments around the world are working out the logistics problems of distributing billions of vaccine doses. It feels like a symbol of the times we are entering into, times that I think will be defined by anti-network effects.

2/ Vaccinations and mask-wearing are examples of anti-network effects. I’ll define these as effects that can slow down, regulate, arrest, or reverse the operation of network effects, and which might themselves be network effects.

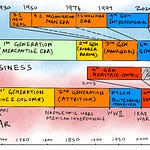

3/ For almost 50 years, since the invention of the PC, the world has been riding one network effect after the other, all of which ride on top of the infrastructural network effect of the internet.

4/ To review, a network effect is when the power of a system grows faster than its size. The original form was called the fax-machine effect. One person with a fax machine is useless. Two people is one connection, three people is 3 potential connections, 4 is 6, and in general n nodes is n(n-1)/2 unique connections. So the power of the network grows as the square of its size.

5/ Network effects in computing infrastructure are deeply connected to Moore’s Law. When computers get cheaper, network nodes get cheaper too, and more things can get attached to computers, and then to each other via the network.

6/ This leads to a double effect. Every 18-36 months, the density of transistors doubles. This makes the cheapest computers based on the cheapest chips much cheaper, and what’s more, this allows whole new classes of even cheaper computer to be invented ever decade or so. So one compounding effect rides another. That’s how we we went from mainframes to Raspberry Pis, and from an internet of 2 computers to an internet of billions.

7/ There’s in fact a third effect. If computers get more powerful at a steady geometric rate, and industrial mass production lag is minimal, then the rate at which the network can grow is itself a function of network size. You don’t have to add 1 node at a time, you can bulk-add n nodes.

8/ Everybody with a home computer already had an internet connection, so with a router, everybody can add a wifi connected device at the same time. With software it’s even easier: everybody with a phone can download an app at nearly the same time, creating near-instantaneous soft networks.

9/ We’ve been riding this triple-punch meta-network effect for nearly 50 years. You’ve got Moore’s law, the basic network effect of devices, and then the network-size-proportionate growth effect. And for people about my age and younger, our entire lives have been spent on this ride. To the point where it is second nature.

10/ This is actually pretty unnatural. Think about the classic brainteaser to teach exponential or geometric thinking. If a lily plant doubles in size every day and on the 30th day covers the whole pond, when did it cover half the pond?

11/ The answer is of course, the day before, on the 29th day, and to people like us, this barely even counts as a brainteaser. In fact, for kids today, I suspect the expected wrong answer, which is the 15th day, will feel unintuitive. They deal with fewer important things that work that way.

12/ There’s a lot more to say about network effects and various formulations like Metcalfe’s Law and Reed’s Law, but we’ve been doing that for my whole life, so enough said. I’ll just add one more point: network effects are pretty dumb. I mean even viruses and lily plants on ponds can embody them.

13/ This is in general not true of anti-network effects. While some anti-network effects are themselves driven by network effects, most work on other principles. So let’s take an inventory.

14/ The first kind of anti-network effect is self-limitation, when a network effect self-neutralizes. For example, once you have had Covid, reinfections are unlikely and you’re immune for a while. This is why you get an S-curve ending in a plateau, though a lot of people have to die along the way.

15/ Then there are anti-network effects that are themselves network effects, but distinct from the original one. Like the idea of wearing a mask spread pretty fast. Faster than the virus itself. The production of masks also spread via network effect. Some people saw others making masks and started imitating their behaviors.

16/ But many important things are not driven by network effects. Like when non-trivial habits have to be adopted. For example, disinfection and washing hands are behaviors that took a really long time to spread, and are still not universal more than a century after germ theory.

17/ Atul Gawande wrote a great essay called Sharing Slow Ideas in the New Yorker in 2013, that talked about innovations that are like this. That don’t spread like wildfire via network effects, but require pretty painful and slow diffusion via deliberate efforts.

18/ The reason slow-spreading non-network effects can sometimes still beat fast-spreading network effects is that they can be governed more intelligently. They are not as dumb as network effects.

19/ For example, it would be nice if we had a really dumb kind of network-effect vaccine that could be transmitted by a cough, via some sort of good virus that can fight the bad virus. Then the two network effects could race each other in a pretty dumb way. Explosion and counter-explosion.

20/ Unfortunately we don’t know how to make that kind of vaccine, that spreads via a network effect. Good things seem to spread slower than bad things in general. Brandolini’s bullshit asymmetry principle is an example: it takes an order of magnitude more effort to refute bullshit than it takes to produce it.

22/ The kind we do know how to make have to be slowly scaled in production, painfully distributed and administered by a small group of trained people. The only reason it has a chance is that we don’t have to be random.

23/ So that’s why governments are being deliberate and strategic in the order in which they vaccinate people. Of course you can be too careful. New York was criticized for expecting senior citizens to complete a complex form with 50 questions and multiple attachments to get vaccinated, and most efforts have now gone much simpler. Still, unlike the virus spread, it’s not dumb or near-random.

24/ You see the effect in computers too. In cyber-warfare, you don’t attempt to shut down the enemy’s capabilities by knocking out random computers in their network. You target key chokepoint routers or undersea cables. If you are an authoritarian government, you install firewall technology at the network edges. So those are anti-network effects that win by being topologically intelligent.

25/ There is a broader theme here: network effects are dumb, indiscriminate and very, very fast. They rely on abundance and target rich-environments. They think one step ahead in time, and one step around in space. But for those very reasons they are also very fragile. They can run out of raw material and starve. They can run into boundaries. They can even be slowed by simple ideas like six-feet separation.

26/ Anti-network effects sometimes incorporate network effects of their own, but are generally more deliberate, intelligent, and actively governed. They are designed with scarcity in mind and are not so easy to starve out. They have long horizons and think many steps ahead in time, and can be spatially intelligent across entire topologies.

27/ They need all these abilities because otherwise network effects have incredible advantages. Anti-network effects are like the tortoise that can eventually catch up with the hare. But because they lack exponentially increasing impact, they need other features to spread.

28/ Things can get worse though. There are network effects that also benefit from intelligence. Well-designed computer viruses are an example. They don’t spread indiscriminately. They can carry a payload of navigational intelligence in space and time and spread very intelligently. This is why countering clever computer viruses is so hard.

29/ There’s one more important class of anti-network effects we haven’t talked about, namely in information flows. After the January 6th storming of the Capitol, we saw how an anti-network effect operated with kinda stunning speed.

30/ The highlights, as you know, were that Donald Trump was suspended from major social media platforms, and Parler was suddenly cut off at the knees by major infrastructure providers. A good reminder that when the topology of a network effect is fragile — in this case the Trump influence network with Trump himself as a single point of failure — what takes years to build up can take minutes to shut down.

31/ That raises other issues I won’t get into, but here I just want to note that the anti-network effect here — simply cutting off a major source of disinformation and noise — was both easy and instantaneously effective. If you’re on Twitter, you’ve probably noticed how much drama has been cut out overnight.

32/ I want to round out this set of examples with another big important class of network effects and their anti-network effects: markets and regulation. Markets are generally based on network effects. Everything from price information to manufacturing capacity to early adoption tends to have a network effect in it. The economy grows via network effects, which is why critics compare it to cancers and viruses.

33/ Anti-network effects in the economy on the other hand, are slower and more deliberate. Anti-trust mechanisms are like taking out a major node once it reaches a certain scale. Monopolies are a special case. In network theory terms, they are a single node cut point, where for example, removing a producer entirely disconnects demand and supply.

34/ The broader theme I’m getting at here is that after 50 years of riding a big meta-network effect, we are entering an era of anti-network effects. Slower, more deliberate, more intelligent phenomena that achieve effects in very different ways.

35/ This is neither a good or bad thing. It is just part of how the world works. In biology, technology, and economics, there seem to be phases of dumb growth driven by network effects, and phases of intelligent regulation driven by anti-network effects.

36/ In a way this is how intelligence evolves. The human brain is like this too. There is a network effect in a baby’s brain during gestation as neurons get very densely interconnected in a pretty dumb way. Then as the baby learns after birth, the connections start getting cut and the ones left behind embody what we think of as intelligence.

37/ There’s going to be a temptation in the next few decades to come at this ideologically, like regulation and damping of network effects is always bad, and network effects are always good. After all that’s the religion the world has run on for 40 years. I’ve been raised on Reagonomics like most of you. But that’s all it is, a religion.

38/ The smart thing to do is to simply start learning the physics of anti-network effects. It is going to be hard for most of us below 50 since we have no memories of a world that was not being driven hard by network effects, but I think we can learn. At least it will be a fun new kind of thinking to get used to. A world in which the lily plant does NOT go from 50% to 100% on the 29th day.

Anti-Network Effects