Good People and Wicked Problems

When effectiveness gets unmoored from morality, it is better to be weird than good

I had an aha! moment recently that helped me figure out what it means to exit the culture wars. Not a high-minded martyr flounce that only looks like an exit, while keeping you as entangled as ever, or a checked-out retreat that cedes stakes and agency for sanity, but an actual exit, where the conflict becomes incapable of co-opting your presence or agency within it. A vaccine of sorts.

The key is to appreciate what happens when good people meet wicked problems, and what to do about your own desire to be good.

By good people, I simply mean people who navigate with reference to a moral compass of good versus evil, try to be more good than evil on balance, and generally manage to convince themselves that they’re succeeding through some mix of social and material proof. Adversaries don’t have to agree, and might even see them as evil, but so long as they believe they’re good, they are “good people” in this model. Having friends agree with your sense of being good is nice, but not necessary for most who sincerely try to be good.

All sincere participants in the culture wars are “good people” by this definition (as we’ll see, many seemingly insincere ones are actually sincere too, in ways they are unconscious of).

Wicked problem is a term of art in complex systems discourses, and refers to a situation that is so complex and full of messy internal contradictions that it resists most efforts at resolution. In its modern sense, the term appears to have been introduced in 1967 by systems scientist C. West Churchman in an editorial in Management Science (an equivalent term is goat rodeo).

Examples of wicked problems include climate change, culture war, and the Middle East.

The Covid19 pandemic, interestingly enough, is big and difficult, but not truly wicked. Moral reasoning does not fail capriciously around it.

Wicked problems tend to have several attributes that are deeply disorienting to good people who navigate by good/evil moral frameworks. Here is a list of ten such attributes:

The “wrong” people frequently end up doing the “right” thing for the “wrong” reasons, while the “right people” motivated by the “right” reasons frequently end up doing the “wrong” thing. This turns the moral calculus into garbage.

Seemingly sensible incentives end up having not just adverse selection effects (selecting for evil when they should select for good) but weirdly perverse effects that change the nature of the problem, such as in the famous cobra effect.

Deserving people go unrewarded or end up punished, while undeserving people get lucky, or get out of jail free, and entirely random people end up having a bigger impact than those earnestly trying to have an impact.

People who expect to be the villains of the drama, and accept that role unexpectedly end up heroes, while people who expect and reluctantly accept hero roles find themselves forced into what they themselves judge to be villainy.

Outcomes end up neither right (good people winning) or wrong (evil people winning) but simply unaccounted for in your thinking: “not even wrong” in a moral sense (notions of good and evil, winning and losing, getting garbled), where you can’t label outcomes as good or evil, leaving you with a sense of moral irresolution.

Stupidity seems to become miraculously adaptive, and survival of the stupidest effects start to overwhelm the system. Prima facie self-defeating behaviors combine in strange ways to turn into unexpected winning behaviors (known as a Double Morton effect).

Rational actors by any definition, operating by any kind of legible logic, start doing worse than random, despite technically correct and powerfully justified “play” by their own standards. Luck simply seems to turn against the systematic.

At the same time, people operating by specious and crackpot logics start being mysteriously effective and “right for the wrong reasons” in a true/false sense. Luck seems to favor the unsystematic and random actors.

The situation even resists clean separation into “problem” and “solution.” All elements of both aspects seem illegibly mixed together in the situation, including the would-be solvers themselves. Every factorization into problem and solution is itself problematic.

Seeing yourself as “part of the solution” gets increasingly challenging, and the harder you try to be certain of your own positions, the more your options for effective agency seem to shrink, and absolute moral clarity seems to result in absolute impotence. Conversely, accepting being seen as part of the problem becomes weirdly empowering, expanding agency.

Broadly, encounters between good people and wicked problems lead to intuitive moral reasoning failing, and unconscious folk models of moral causation unraveling.

Firm moral ground beneath your feet seems to liquify the moment you try to act.

Here I mean beliefs and postures like “the world ought to be just,” or “try to be compassionate” or “do better.” I am not talking about formal ethical reasoning of the sort academic philosophers indulge in (what I like to call spherical morality cows).

The result is like the situation in the meme: the distraught screaming woman is the condition of the good person. The confused cat is the wicked problem — the cat cannot see the moral map the distraught woman is using, and the map is too wrong for the cat to see reality in any alternative consistent way.

To the extent the wicked problem represents a state in the system’s emergent self-awareness of itself, there is no informational pathway for it to mirror the moral map of any particular constituent part.

If you’ve ever tried teaching a cat to be “good” you understand the problem.

Why do humans navigate by good and evil at all if the resulting maps can go so not-even-wrong? In what situations, if any, are moral frameworks adaptive at all?

I call these situations moral dry ground. Not high ground, dry ground. Where the firm solidity beneath your feet is not liquefying into a confused, wicked, ambiguity.

Moral Dry Ground

It seems obvious to me that moral reasoning is at least adaptive in fairly simple, small-scale, low-tech situations that correspond to primarily social problems with a long history in our evolutionary past. This kind of problem is the core of the dry ground of moral reasoning.

If you’re an early hominid in an early hominid troop, most of your problems in life have to do with what the other 25-30 hominids are up to. The survival strategy of any social species is to trade some material problems — food, safety, shelter — for social ones. We apes seem to have bet our survival on this trade to a wholly remarkable degree. The extremity of our bet on sociability as a survival strategy is rivaled only by social insects.

To a first approximation, dividing your social world into good and evil hominids gets you halfway to solving most problems. You solve problems by competing, cooperating, detecting cheating, and litigating political status. It is more important to understand the other apes than it is to understand the world. And you do it all by thinking in terms of good and evil, and picking your alliances and battles accordingly. To the extent technology plays a role in your problems, it is sticks-and-stones grade technology, and also handled socially, through imitation and social learning. The causal models required to understand technology are not complex. Pokey sticks make you bleed. Fire burns. A well-aimed rock can knock out bad people and prey.

I am not an ethologist and don’t want to belabor this point, but I suspect something like this picture is true. Moral reasoning frameworks are likely at least effective and adaptive in small, primitive social settings, where social aspects are much more sophisticated than technological aspects, and all scales are small. If they weren’t they wouldn’t have evolved.

The question is, are they effective and adaptive beyond that?

I submit that they are generally not, but there is no sharp threshold of social scale and technological development beyond which they reliably fail either.

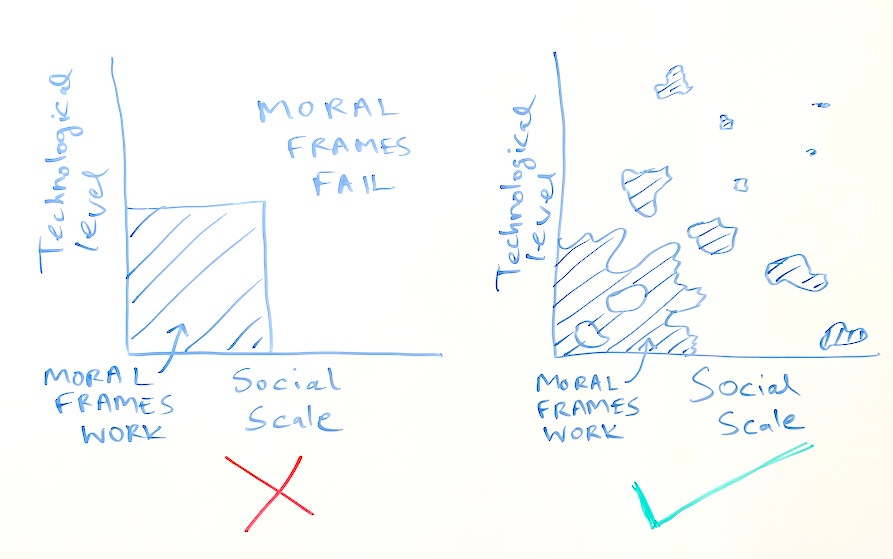

While few beyond sincerely religious people believe good vs. evil frames are universally applicable, many otherwise sophisticated people seem to think of the boundary between simple and complex along social/technological dimensions as a clear one, like the picture on the left, while the actual situation tends to be more like the picture on the right.

So moral reasoning doesn’t really fail outright beyond a particular point of socio-technical complexity, but it becomes increasingly unreliable. The islands of comprehensible moral order in an increasingly complex world get smaller, farther apart, and more unpredictably located.

Large, connected, coherent regions of moral order, with boundaries far enough away to be ignored, give way to fragmented patches of moral order where things go badly wrong if you tweak parameters even a little.

We can distinguish three postures and outcomes in such complex worlds:

Absolute moralists fail absolutely, the way flat earthers do trying to navigate a round world.

Moral relativists fail the way people far inland do — they may not believe the world is flat, but they can see no large water bodies within their horizons, and begin to unconsciously operate with a totalizing mental model of “the world is mostly firm land” (moral dry ground).

People who abandon moral frames as primary frames and look for alternative frames have a shot at being effective, but have no guarantees. These are people who realize 3/4 of the world is covered in water, and try to develop aquatic modes of being, giving up reliance on moral dry ground altogether.

One way to think about this is: complex worlds are unpredictably, locally, karmic.

Things would be easy if life were never fair; if reward and punishment never correlated with behavior; if material cause and effect always ran aground in weird phenomena; if heroes and villains never played their expected roles.

The problem with complex systems is that they occasionally, unpredictably, do behave in accordance with expectations within moral frameworks. Not least because moral frameworks tend to act as self-fulfilling prophecies if enough people abide by them, and only associate with others who share their frameworks.

The problem is that these frameworks work often enough to keep you attached to favored moral behaviors, but not reliably or powerfully enough to resolve wicked problems. As with any pattern of intermittent positive reinforcement, the result is attachment to patterns of activity rather than outcomes.

The reason this happens with wicked problems, of course, is that they tend to be large in scope and complexity, and span many islands of local karmic predictability, and vast oceans of phenomenology where no moral framework seems to even apply, let alone work. The picture looks a bit like this:

The problem isn’t just that moral frameworks cover only a small fraction of the scope of the problem (“dry land”) — let’s generously estimate it to be 30%. The problem is that what dry land there is exists in the form of mutually incompatible islands with conflicting definitions of good and evil that cannot be reconciled in the context of the problem.

The last feature is important. Normally, when we are in simple regimes, with moral dry ground as far as the eye can see in all directions, we can pretend there are no inconsistencies across frameworks, and that all point to roughly the same conclusions.

This triggers admirable ecumenical sentiments in people. Moralists are wont to say things like “all great religions point to the same great truths like love and peace and universal brotherhood.”

But once a wicked problem complicates the situation by expanding the scope and increasing the complexity, the frameworks start coming into conflict with each other, and with their own limits where dry ground gives way to liquid ambiguity.

Moral Ambiguity and Affective Computing

An important feature of moral frameworks is that they can be deployed in robustly intuitive ways, with reference to one’s own feelings, and via appeal to (or manipulation of) others’ feelings. You do not need a great deal of training to act morally, or to influence or be influenced via moral modes.

Moral frameworks are typically tractable enough to be navigated with what one might call moral computation. By which I don’t mean things like the trolley problem, but something like going by gut feel. A primarily affective “System 1” mindset.

In simple contexts, the more morally self-certain you feel, the more likely it is that your response to a situation will be adaptive.

Self-righteousness and moral self-certainty are adaptive in simple situations.

You may not like this kind of person, but if the situation is simple, chances are they’ll survive and thrive, while people sensitive to moral ambiguities and oceans of amoral mystery will overthink situations and respond poorly.

In other words, simple situations reward those who feel, and punish those who think.

But when things get complex, and problems get wicked, things flip around.

As Horace Walpole said around 1776, when the world was first starting to get wickedly complex, “the world is a comedy for those that think; a tragedy to those that feel.”

Note a crucial point: this does not relate to how good you are at either, but which mode of responding to the world you naturally prefer. One does not have to be a good thinker to respond to the world primarily through thought. Or possess refined emotional sensibilities to respond primarily through feelings.

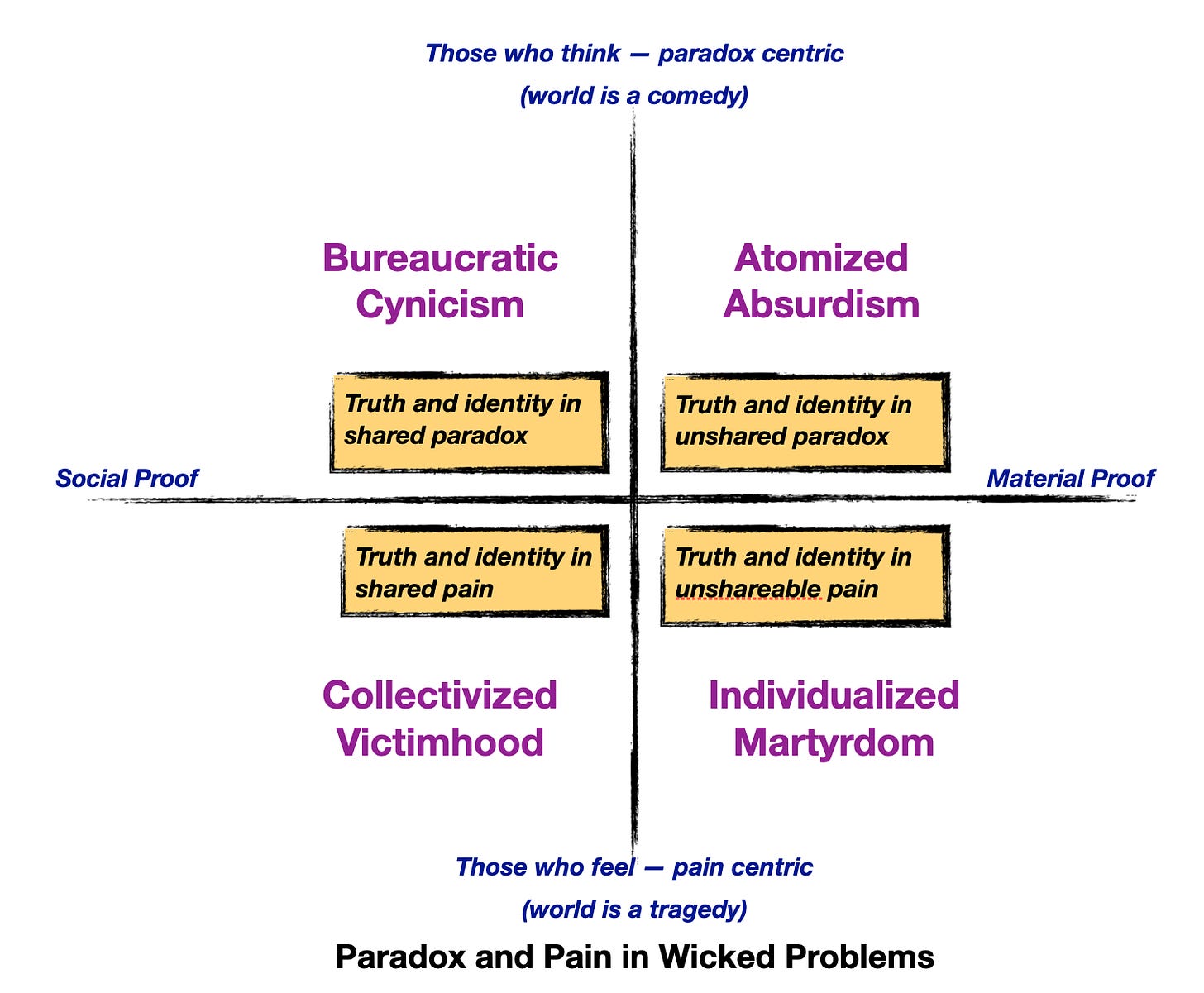

This feel/think dichotomy gives us one axis of a 2x2 I made up, to illustrate the conditions induced by the postures you might adopt within a wicked problem.

The key is to recognize that a sense of comedy rests on sensitivity to paradox in a situation, while a sense of tragedy rests on sensitivity to pain in a situation.

The two key dimensions of complexity — social scale and technological complexity — now map to the two limits of the x axis here. If you pay attention primarily to the social aspects of a situation, and are sensitive to social proof, you will seek truth and identity in collectivized forms (the left half). If you pay attention primarily to material aspects of a situation, you will seek truth and identity in individualized forms.

Now of course, a wicked problem defeats intuitions on both fronts, which means things are going to go wrong for you, or worse, not-even-wrong. But how you respond to things going wrong is a function of whether you are a feeler or a thinker (and remember, you don’t have to be good at it; merely prefer it).

If you’re a feeler (bottom half), you’ll respond by focusing on the pain in the situation. I like to distinguish between victim and martyr versions of responding to pain. A victim focuses on shared pain that others clearly feel as well, and finds solace and agency in connection. A martyr focuses on what seems to them to be unshareable pain; something they must navigate on their own, which nobody else can understand, and finds solace and agency in individual spiritual striving. You often find victims on the political left, and martyrs on the political right of wicked problems.

If you’re a thinker (top half) on the other hand, you will respond to things going wrong or not-even-wrong by focusing on the paradoxes in a situation. Again, if you focus on a shared sense of paradox, you land in what I think of as bureaucratic cynicism, sensitive to the darkly humorous contradictions induced by institutional structures. If you focus on what seems to be an unshareable sense of paradox, you end up in atomized absurdism.

If we map these four postures to archetypes, we find that both victimhood and martyrdom are feeler responses, and map to the distraught screaming woman in the meme. The atomized absurdism archetype is clearly the cat in the meme.

But we have a new archetype now: an identity built around a shared sense of paradox creates a personality that is something like Sir Humphrey Appleby in Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister. A self-described “moral vacuum” who exults in the paradoxes of governance and bureaucracy, and has been reduced to self-aware cynicism by decades as a civil servant. He is focused entirely on means and has become blind to ends.

Which of these four responses is the most adaptive in a complex system in the throes of a wicked problem?

Well it’s a 2x2, so obviously the right answer — not in a good or evil sense, but in a true/false sense — is the upper-right quadrant.

But why?

Becoming Part of the Problem

If you’re an attentive reader, you’ll notice I’ve pulled a bit of a switcheroo. I began this essay by mapping the cat in the meme to the wicked problem. Now I am mapping it to an archetypal response to the problem.

Which is it?

Both.

As a motif of the wicked problem, the befuddled cat is a complex system, with some sentient features, that can neither comprehend moral maps actors within it are using to navigate it, nor independently embody what those maps point to, because the maps don’t point to anything.

As an archetypal response, however, the befuddled cat represents what one might call a holographic response to the system (being all holographic about everything is popular with systems people; it is our favorite form of magical thinking). The part embodies the whole.

You try to fractally be the problem, and allow yourself to be governed by its logic, exercising whatever agency that posture offers, without expecting it to always make sense.

And in doing so, you take on all the befuddling attributes of the problem itself — the list I offered earlier in the essay. Go back and re-read that list. What might it mean to embody those attributes as a person acting within a wicked problem? (The correct answer is Yossarian; somebody who is empowered by Catch 22 rather than trapped by it).

As in the other three quadrants, pain and paradox may be thought and feeling stoppers. But unlike in the other three quadrants, they are less likely to turn into action stoppers, because you’re not bound by an inescapable urge to make moral sense within a preferred moral framework.

In the bottom half of the 2x2, featuring the feeling, tragic actors, being part of the problem is a bad thing. You want to embody good, externalize evil, set up a contest between good and evil, and win it. You see yourself as part of the solution, and the evil side as the largest part of the problem.

In the top half, you recognize you are part of the situation, and therefore part of the wicked problem, but that this mereological condition admits no meaningful moral readings. It just is. The question is — what do you do about it.

The Humphery Appleby response is not a terrible one. It is a kind of institutional pragmatism that makes for extreme effectiveness under some conditions. Bureaucratic cynicism is conducive to effectiveness in the presence of moral ambiguity, within moral mazes that are challenging to navigate but not wickedly so.

As Appleby points out repeatedly through the show, as a civil servant committed to serving democratically elected political masters of opposed ideologies through a long career, trying to actually “believe” in policies you are charged with implementing, at a moral level, is a recipe for schizophrenia. If you serve conservatives today, but might have to serve progressives tomorrow, and then conservatives again in four years, you can’t coherently function as a true believer. So it is hardly surprising that you are liable to become attached to means and blind to ends.

The problem with bureaucratic cynicism though, is that institutions tend to have their own native moral frameworks that is invisible (“this is water”) to those who occupy them. Humphrey Appleby was neither truly Tory, nor Labor, but he definitely abided by the implicit morality of the British Civil Service. What in the show is generally described in terms of the ultimate character trait of “soundness,” which is, in essence, a predictable commitment to institutional stability and self-perpetuation, in accordance with the Iron Law of Bureaucracy.

A notion like “soundness” (and its equivalents in other institutions) is not so much a True North on a moral compass as it is a mark of being attuned to an illegible moral environment without being conscious of it. This is one reason the idea of keeping politics out of an organization is ill-posed — you can only keep out the politics that you are conscious of. But the idea of prioritizing institutional stability and self-perpetuation, which is usually the unacknowledged intent, is a well-posed one (whether or not it is morally justifiable in a specific case). “Politics” then becomes any idea that threatens either stability or self-perpetuation.

After all, if the existence of the institution is not assumed, the idea of a political “inside” and “outside” is moot. It is not that the organization cannot change, but that it cannot change in way that does not allow for continuity in identity.

In a complex world, in a situation shaped by wicked problems, this limitation on acceptable change may be impossible to respect.

Notably, the original show reflected the political realities of Thatcherite Britain, and Thatcherism did end up significantly altering the nature of the British Civil Service, in ways that make the Appleby archetype something of an anachronism today. In the 21st century reboot, The Thick of It, Peter Capaldi plays Malcolm Tucker, a sort of latter-day Humphrey Appleby who operates in ways that make it clear that it is a brave new world, with no real place for the Applebys of the world.

And in a post-Brexit, post-Great-Weirding Britain shaped by the likes of Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings, even the Capaldi version of the archetype seems anachronistic.

In a complex world, wicked problems can stay wicked longer than bureaucratic cynics can keep their institutions stable, and their own identities unchanged.

Outgrowing the Culture Wars

Let me return to the question I opened with — exiting the culture wars. Clearly, I am suggesting that the way to do that is to be the cat in the meme. A holographic part of the problem defined by atomized absurdism.

Interestingly, one of my earliest explicit tweets about the culture wars, as far as I can tell was a 2015 joke about unsubbing from them (the joke being, of course, that one does not simply unsubscribe from the culture wars):

This was less about the stress of conflict (which I can tolerate to a fairly high degree) and more a reaction to what seemed to me to be a self-evidently futile activity for me. I developed the thesis that the culture wars were futile activities pursued for their own sake in my 2020 article, The Internet of Beefs, but I never did quite figure out what it means to get out of them.

Until now.

Many mistake exit in the sense of Albert O. Hirschman’s Exit, Loyalty, and Voice, as a mode of exit from the culture wars. It is not.

In the context of a wicked problem, a Hirschman exit is a form of theatrical, self-aggrandizing martyrdom; a form of voice.

So why is the cat a true exit position?

In terms of the 2x2, the culture wars are a three-way conflict between victims, martyrs, and bureaucrats. All three operate within moral frameworks, and are predictably plottable on each other’s moral maps. All three have clearly declared intentions towards each other, as illustrated by the arrows.

The last group is insincere relative to the explicit moral frames in play, but bound by the implicit ones induced by the organizations they are attempting to perpetuate.

You exit a wicked problem not when you adopt what you think is an unassailable posture “outside” of it on a particular moral map, but when nobody can reliably classify you for long enough to consider you either a friend or foe on any map.

To be the cat is to be unclassifiable in any of the three roles.

Like the wicked problem itself, which you are trying to holographically embody, you are not a predictable part of the picture, who can be reliably located on the maps of strident moralizers. To the extent you’re present in the story at all, you are present as a trickster, rather than as hero or villain. Content to be misunderstood rather than cast as good or evil.

You remain in the situation defined by the wicked problem (because almost by definition there is no exiting it) but are no longer bound by anyone’s moral maps of it. You might make occasional use of fragmented, local moral maps, but you don’t primarily navigate with a moral compass anymore.

Because moral compasses don’t work on wicked problems. That’s what makes them wicked. The only way out of a wicked problem like the culture wars is to break out of addiction to being “good” and seen as such; to being a “part of the solution.”

To those who remain bound by them, you will not seem immoral. Instead, you will seem weirdly confused, weak-willed, morally compromised, and inconsistent (if they are inclined to be contemptuous of you) or unpredictably and amorally sociopathic (if they are inclined to fear you). Either way, they will not be able to reliably classify you.

Because the maps of the stridently moral only work to locate people who are as stuck as themselves, trapped by the wicked problem, unable to act or move.

Where you act, you will be seen as muddling through messily, with your actions leading to wildly conflicting interpretations but mysteriously accumulating effects.

If you’re ever accused by opposed factions of being contradictory things (I have often been simultaneously accused of a Marxist and a capitalist for the same article), there’s a good chance you’ve broken through to a degree.

You can’t expect to break through absolutely or permanently — an amoral map of a wicked problem offers no zones of pure moral ambiguity for you to enjoy your own ineffable moral nebulosity.

But you can expect to be more effective.

Some of the time.

there's a part of me thats (relatively) well-read on ethical philosophy brain is getting annoyed at how you're using the word "moral" here to describe our inherited moral instincts as opposed to a coherent philosophy or goal

i don't think that going meta on a moral question and acknowledging ambiguity cuz complexity means giving up on morality. infact i'd suggest that it indicates moral growth/maturity. take for example effective altruists (who definitely have a moral compass). their entire approach is "the usual way to do good in the world sucks, lets try to move to a more effective way even if it conflicts with our instincts"

i do think that being uncategorizable by various camps is a sign you're doing something right (because so many of them tend to have high modernist assumptions about how the world works and we need to move beyond that ASAP), but as with every metric you don't want to turn it into a goal. illegibility for the sake of illegibility leads you straight into postmodernist obscurantism

While clearly a distinct concept, the cat quadrant strikes me as antifragility-adjacent. It occupies the same conceptual quadrant, along with wu wei.