I almost never get to write about my consulting projects due to NDAs, but my work over the last year on the Summer of Protocols is a rare exception. It is also a project that has produced a lot of broadly accessible output that makes sense to share with a general audience. Most of the content of my consulting work, by contrast, would probably be too specialized and/or boring to general audiences even if I could share it.

In fact, there’s almost too much to share — over 400 pages worth of research output that we’re just beginning to publish. And since I had significant influence over both the selection of funded projects and the course of the research itself, a lot of what came out of it reflects my own personal interests and priorities. So I suspect if you enjoy reading my writing, you’ll enjoy the output of this whole program. It’s all stuff I’d have wanted to research and write about myself if I’d had the various aptitudes and perspectives it actually took.

In the first half of this newsletter, with my program director/frontman hat on, I want to provide a quick overview of the program and its output. In the second half, with my newsletter writer hat back on, I want to try and place this work in the larger context of things going on in technology and the world at large.

Specifically I want to riff on the idea of hardness (both as in diamonds, and as in difficulty) introduced by Josh Stark in his essay Atoms, Institutions, Blockchains. The study of protocols, I’ve become convinced, is the study of hardness in Josh’s sense, and this idea feels like it should be the True North not just for the brewing new cycle of technology deployment in the crypto world, but for protocols more generally. Everything from climate and nuclear launch protocols to party planning and UX design is a search for hardness in an uncertain world. The search for hardness is going to shape the future of the world at large.

But first, let’s survey the bountiful harvest from the summer program.

I. The Protocol Kit

Last week, a lot of hard work by a lot of people over the year culminated in the launch of the Protocol Kit. This is the form in which we’re publishing all the summer research, plus more.

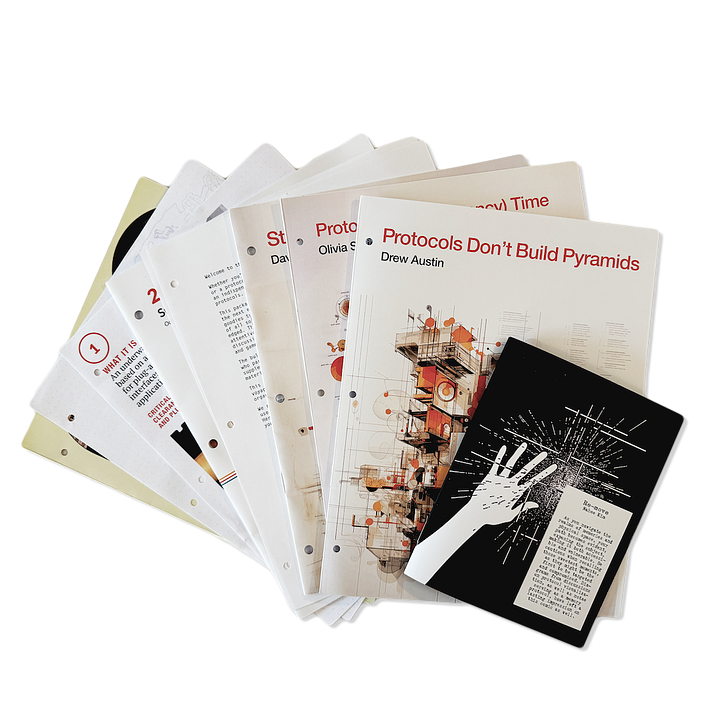

The kit is a completely free digital/physical open publication, published as a series of six modules, each with 10-14 items, under an open license. It includes essays, artwork, games, workshopping tools, posters, and a lot more. We hope it helps spark a thriving scene around the study of protocols.

The first module has been published, and available to read online. The remaining modules will be published over the next 6-8 months, one every few weeks. There is a total of around 80 pieces cued up in the publishing queue.

Physical kits will be mailed out as sets of inserts for a lovely 3-ring binder (I am personally looking forward to getting mine, since I haven’t organized my studying/research in 3-ring binders since I left academia 17 years ago). These physical kits are not for sale, but a total of 512 kits will be distributed for free to people and organizations at the frontiers of protocol work. And by that I mean any kind of protocol.

If you work on protocols of any sort, as a researcher, entrepreneur, artist, technologist, or evangelist, this kit is for you. The physical kit will be especially valuable for those want to do focused, deeper protocol work in 2024.

You can request one of the limited number of free physical kits via the form on the kit page. Of course, even if you don’t snag one of the physical kits, you can access all the research online as it is published (and print out the material to make your own physical kit if you want). You can also attend our Protocol Town Halls to learn more directly from both our researchers and guest speakers (it's a summer program, but with an active off-season calendar of biweekly salons and active discussions).

I ran the Sumer of Protocols program along with Tim Beiko and Josh Davis of the Ethereum Foundation, which funded it, with Jenna Dixon joining in for editorial support in Fall for the ongoing publication phase. All credit for the beautiful production work goes to them.

The program funded 33 researchers to work on all kinds of protocol-themed projects. In the first module, for instance, you’ll find an essay on protocols in urbanism by Drew Austin, another on the history of standards making by David Lang, a surreal graphic novel about memory protocols by Nahee Kim, a nerdy poster explaining a new underwater connector standard, and several other goodies. The thematic scope of the research ended up being truly vast. Protocols touch every aspect of life, and it shows when you attempt to study them.

If you’d like to keep up with the program (we’re currently in an active off-season), sign up for the Protocolized newsletter, where we share updates, new research releases, and upcoming event information. Please share this post with anyone you think should be aware of it. And do share any of the research that you find interesting with friends and colleagues. We’re relying a lot on word-of-mouth to get all this work to the people who are most likely to get something out of it.

Also, a request: If there’s an intersection between your world and this work, consider inviting one or more of the researchers for podcasts, speaking/writing opportunities, and such. Browse the research, and get in touch with me if you’d like introductions. Tim Beiko and I already did a couple of podcasts at a program level. We went on the general interest Infinite Loops podcast and on the more crypto-focused Greenpill podcast. While we might do a couple more from our managerial perspective, we want to try and focus the spotlight on the actual individual bits of research and the researchers who did the work.

I’ll switch hats now, and talk about why protocols, why now, and why hardness as a true north. What follows is a more personal take, so others who participated in the program may or may not agree with me.

II. The Soul of Protocols

One thing that really got driven home for all of us over the summer is that protocols are a very broad and old category of socio-technical phenomena. For instance, memory technologies understood as protocols, the focus of Kei Kreutler’s project (to be published in Module 2) go back millennia and occur in every culture.

But it’s only in the last 50 years or so, with the rise of communications technologies, especially the internet and container shipping, and the emergence of unprecedented planet-scale coordination problems like climate action, that protocols truly came into focus as first-class phenomena in our world; the sine qua non of modernity. The word itself is less than a couple of centuries old.

And it wasn’t until the invention of blockchains in 2009 that they truly came into their own as phenomena with their own unique technological and social characteristics, distinct from other things like machines, institutions, processes, or even algorithms.

The discussions that led to this program started with problems, such as protocol ossification, that initially seemed specific to blockchains, but quickly turned into very general problems that seemed to crop up around anything that can be considered a protocol, which is almost everything.

We spent a good fraction of the summer arguing about competing definitions of protocols, and about distinctions between protocols and adjacent concepts like institutions, rituals, APIs, and conventions. If you dive into the research output and recorded talks, you’ll get a taste of these conversations. Part of the point of the kit is to help others speedrun the learning curve to basic protocol literacy and acquire the conversational competence to get to the interesting questions in weeks, rather than the months it took us.

We’re still diverging and disagreeing as far as definitions, distinctions, and ontologies around protocols go, but the discourse has evolved from frustrating to generative, and has expanded from a half-dozen people groping blindly to several dozen people able to view the world with protocol-tinted goggles (protocol vision would be a good idea for an AR headset app — highlighting the elements of protocols and standards that surround us all the time; all the ghosts in all the machines we inhabit. There are at least a couple of dozen protocols of various sorts between me typing these words and you reading them, many of them subtly present on whatever screen you’re reading on).

For me, one of the biggest changes in my thinking between February 2023, when I co-authored the pilot study that kicked off the program, The Unreasonable Sufficiency of Protocols (a final version will be in Module 2 of the kit) and today, 10 months later, is a strong re-orientation around Josh’s concept of hardness. It was in peripheral vision in February, and is front and center now.

So what is hardness? Hardness is to protocols as information is to computing, or intelligence to AI. I’ll block quote Josh’s original take (specific to blockchains, but applicable to all kinds of protocols) here:

Although humans have been creating and using information technologies like writing, printing, and telegrams for hundreds or thousands of years, it was only in the last century that we articulated clearly what all of these things have in common, and realized that they can be understood as a category.

In the decades since, the idea of information has spread into mass culture. Today, it is intuitive to most people that speech, images, films, writing, DNA, and software are all just different kinds of information.

I believe that a similar situation exists today with respect to blockchains. A new technology has forced us to reconsider things we thought we understood. But instead of books, telephones, and voices, this time it is money, law, and government. We can sense the outline of a category that unites these seemingly disparate things.

Perhaps there is an analog to information hidden in the foundations of our civilization. An abstract property that once revealed, might help remake our understanding of the world, and help us answer plainly what problem blockchains are supposed to solve.

Call this property hardness.

Human civilization depends in part on our ability to make the future more certain in specific ways.

Fixed, hard points across time that let us make the world more predictable.

We need these hard points because it is impossible to coordinate at scale without them. Money doesn’t work unless there is a degree of certainty it will still be valuable in the future. Trade is very risky if there isn’t confidence that parties will follow their commitments.

The bonds of social and family ties can only reach so far through space and time, and so we have found other means of creating certainty and stability in relationships stretching far across the social graph. Throughout history we have found ways to make the future more certain, creating constants that are stable enough to rely upon.

In recent conversations with Josh, it’s clear his own thinking on hardness is evolving (I’ve been urging him to turn the essay into a book), but the concept is I think important enough that more people should be thinking about it.

The analogy to “information” is very powerful. “Hardness” is in the same category of conceptual generality. In a recent talk, Josh self-deprecatingly noted that he was no Claude Shannon, but whoever ends up working it out (it will probably take a collective effort of many minds), I think there’s something as powerful as Shannon’s notion of information lurking beneath the surface of Josh’s preliminary account of hardness (a good alternative title for his essay would be Prolegomena to Any Future Hardness Theory).

Protocols are engineered hardness, and in that, they’re similar to other hard, enduring things, ranging from diamonds and monuments to high-inertia institutions and constitutions.

But modern protocols are more than that. They’re not just engineered hardness, they are programmable, intangible hardness. They are dynamic and evolvable. And we hope they are systematically ossifiable for durability. They are the built environment of digital modernity.

This is obvious when you think about what you can do with blockchains specifically, but the powerful generality of the idea becomes obvious when you look at other domains. Drew Austin’s essay teases out the “protocol layer” between the hard materialities and soft sociologies of urban environments (think programmable traffic lights). Sarah Friend’s project on death protocols (coming in Module 6 of the kit) examines the dissolution of hardness in the definition of life itself, including digital life, through the lens of how we construct the end of it (think closing and porting a social media account off a dying platform).

This is deep stuff. And I’m not someone who easily admits stuff is deep, or that I’m out of my depth.

When I first wrote about this work 9 months ago (The Bones of Time, March 10), I had a vague intuition that hardness matters in ways I didn’t quite grasp. The headline of that newsletter is a reference to Bruce Sterling’s phrase “the mathematical bones of reality,” and my poetic premonition at the time was that protocols are in some sense the bones of time. They create hardness across the past, present, and future. Right now, our vocabulary for talking about the bones of time is fragmented, pointillist, and mostly poetic. We talk in terms of “intentions” and “plans” for the future, “to-do lists” and “priorities” for the present, and “canon” and “tradition” for the past. We clumsily talk about hardness through the inappropriate vocabulary of uncertainty and risk.

Underneath it all, there is hardness, or at least, a search for hardness. Sometimes we find it, often in unexpected places, and figure out new ways of building with it. Other times, we get taken in by mere illusions of hardness, and construct dangerous reality distortion fields of pseudo-hardness around ourselves (the Dangerous Protocols project by Nadia Asparouhova, coming in Module 3, explores the dangers of protocols, and at our retreat, she came up with the notion of “Kafka protocols” as a thought experiment for exploring oppressively reality-distorting regimes of protocol design space).

You get fresh insight into almost anything, even the most nebulous things, if you come at it from the perspective of protocols and hardness.

Take the idea of the so-called “meaning crisis” for instance, and the associated upsurge of interest in rituals. This is about as far away as you can get from canonical technical protocol problems like getting computers to talk to each other through TCP/IP.

The meaning crisis, I think, is a search for the solace of hardness in anomie, and the frustrated impulse to construct protocols to harness it against existential angst. Anomie, revealingly, is usually defined as there being too little or too much structure to life, and you could improve that definition by replacing structure with hardness.

Try it. Pick any murky problem or phenomenon. Ask: where is the hardness, and what’s the protocol for harnessing it? You should end up with interesting insights.

But is there practical value here, or is hardness merely a satisfying appreciative lens on things? Why should you think explicitly in terms of hardness and protocols in whatever you’re doing? What’s the upside?

For one group of people, the relevance is immediate. If you work on actual protocols of any sort, whether it is carbon-trading protocols, crypto protocols, diplomatic protocols, AI-safety protocols, or internet standards, thinking about your challenges generally, in terms of “hardness engineering” is a powerful move for both analysis and synthesis. It gets you out of situationally specific and siloed thinking. Some questions you might ask:

Where is the hardness in the structures you’re engineering?

Where is the complementary softness?

What’s the hard/soft yin-yang dynamic?

What is the natural source of hardness you’re harnessing? Diamonds? Cryptography? The law? Guns? A high-inertia game-theoretic equilibrium? A law of physics?

Is the hardness sufficient to serve the purpose? Should you perhaps swap in a stronger source of hardness? Is it too much? Should you reduce the level of hardness?

Has a new source of hardness been recently discovered? Can you redesign a protocol to use a new source of hardness?

A very good current example domain where this relevance is obvious is in privacy engineering. It’s a domain that’s already at the forefront of cryptography applications, but for lots of things we want to be able to do with privacy, current sources of hardness, such as vanilla public-key encryption, are not enough (they’re too hard). But modern zero-knowledge (zk) proof technology is a whole new source of hardness that allows much more flexible privacy engineering. What the folks at 0xParc, a group that’s researching and evangelizing zero-knowledge technologies, call programmable cryptography is a specific kind of programmable hardness.

It’s interesting that the underlying mathematics of zk proofs has been known since the 80s, but it’s only in the last few years that zero-knowledge proofs have been turned into a programmable hardness technology. It’s not just that we have better computers now; we are more protocol literate now, and get the point of zk technologies, and how to use it to engineer better kinds of hardness.

But you don’t have to get this esoteric. More people work on protocols and engineering hardness than probably realize it, and I suspect it would do them a world of good to become conscious of the fact. Protocol thinking offers a level-up in just about any game.

For example, a party planner works on protocols for a good time, and inserts hardness into the proceedings using furniture, props, gifts/favors, lighting, and sound (ever been at an event where the organizer uses a bell, cymbal, or champagne flute to aurally mark sharp boundaries in time?). Could thinking explicitly in terms of protocols and hardness make for better parties? Mashal Waqar built a game (coming in Module 4) around exactly that idea, focused on gifting protocols in the Middle East.

This sort of thing is everywhere you look. Managers engineer hardness into workflows with program management scaffolding and meeting norms. Military leaders engineer hardness into operations to allow for the right mix of fluid responsiveness and hard-edged decisiveness in outcomes. Sports coaches inject hardness into performance through training drills, and individual athletes and teams with the right kind of foundational hardness seem to elevate their sports to whole new levels. AI product designers engineer hardness into the behavior of black-boxed shoggoths with UX guardrails built from RLHF (which you can think of as hardness created via a sharp human-selected classifier boundary).

It’s all hardness engineering, and the solution is always protocols that put the right amounts of hardness in the right places at the right times. And it’s almost always enlightening and useful to explicitly think of problems that way. And when you find a new kind of relevant hardness, you can almost always harness it to improve things.

Interestingly, the hardness frame is as valuable for very simple problems as it is for complex ones. My favorite protocol in recent weeks has been the one implemented in ATMs that forces you to take your card back before dispensing cash. A simple re-ordering of actions to create a spot of hardness where there was previously an annoying softness (remembering to take your card). That’s something I really like about hardness and protocols. It’s a frame that applies at all scales from simple to complex. A big red flag for me is when theories and frameworks seem to only apply at lofty and “important” scales, with simpler scales being ignored as unimportant “details.” Great frames are often deceptively simple-seeming in both theory and practice, can be applied at any scale, and end up having tasteful and sophisticated effects.

Speaking of lofty and important scales, modern AI is an area that really screams for more tasteful and sophisticated hardness engineering and protocol development, with multi-scale attention. And we already got started thinking about it over the summer. Eric Alston and his collaborators investigated one potentially fruitful direction: Killswitch protocols (coming in Module 5). I suspect a hardness/protocols approach to AI safety will blow other approaches (including, uhh… certain theologically inspired ones) out of the water. “Alignment” strikes me as a fragile, narrow, overly restrictive, and ultimately doomed formulation of a much broader class of hardness engineering and protocol development problems.

Speaking of AI, I’ve been nursing this thought that AI and crypto are like the First and Second Foundations of our technological future, together building a pathway out of the desolation of the collapsing industrial age. I just came up with another metaphor for the relationship that I like: AI cuts, crypto chooses. It’s the balance-of-power protocol that will govern the planet in the coming decades.

In practically any domain, I find, thinking in terms of protocols and explicitly searching for hardness to work with is an immensely generative thing to do. It helps get immediate problems unstuck, and it helps you see creative and expansive options.

I think this is because engineering with hardness is a more artistic and fluid cousin of engineering with constraints. In traditional engineering, you’re taught to think in terms of the dimensionality of problems, and to use thoughtfully placed constraints to lower it to tractable levels. Similarly, in art, constraints (such as being forced to work on rectangular canvases with oil paints) are often seen as having a liberating effect on creativity. Hardness is that sort of thinking on a more elevated level, and protocols are the engineered artworks that result from doing it well.

Perhaps sufficiently protocolized technologies are indistinguishable from art.

I’ll stop here for now. I have a lot more thoughts obviously. You don’t spend a year thinking about a topic this rich and run out of thoughts about it in a single essay. I’m sure all the researchers who were part of the program have similarly over-full hoppers of things to say.

I’ll probably be referring in passing to a lot of specific bits and pieces of the research from this year in my own writing in 2024, but if I’m your only connection/bridge to the world of protocols, I strongly suggest you dive in and begin exploring for yourself and reading others. This emerging world is too vast and consequential for one perspective on it to be enough.

This is rather odd, if you stop to think about it. Why do protocols feel like an emerging world even though they’re clearly not?

Despite its antiquity and size, and despite all the recent drama around modern crypto technologies, the world of protocols is a strangely hidden one. Even though there are hundreds of millions of people around the world who explicitly organize their work and thinking around protocols of various sorts, the language of protocols is not a familiar one. It is easier to look through protocols than at them. It is easier to act through protocols than on them. It is easier to systematize an emergent local practice into a bespoke local protocol than to think about the general features of all protocols.

I think this is partly because protocols are evolving from an artisan craft to an engineering and art domain. But it’s mainly because of their very nature.

The language of protocols is an esoteric one for navigating a hidden (and at the risk of sounding cliched, liminal) world that prefers to stay hidden, in part because it deals in the civilizational techno-unconscious. The invisibility of protocols is a core feature. There’s a reason A. N. Whitehead’s famous line, “Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them” became the de facto motto of the Summer of Protocols. Thinking about protocols, you get a sense of a landscape of invisible, inviolable hardness all around us, that shapes our behaviors without our being quite aware of it. A landscape you can learn to see, shape, and violate if you learn the language.

But though the language is esoteric, it is learnable, and though the hardness seems inviolable, it is hackable. And though the world is hidden, it is accessible if you know where the portals are located. And I think the protocol kit is a particularly good portal.

As we head towards the holiday week, and into the new year, I hope you’ll step through the portal, and make exploring this hidden world part of your 2024 plans.

Awesome read!

I think the comparison with Shannon + information theory is apt. Hardness feels like an extension of the Shannon-Weaver model, except the receiver/destination is also the future (and past) and the noise is time (https://blog.simondlr.com/posts/time-as-platform).

We can more effectively communicate with the future and past if we reduce the optionality (possible entropy) at a specific layer. A legal contract for example defines desired behaviour of the participants in the future such that breaking the agreement would be at cost to the participants. This means that some future becomes more possible as a result.

Hardness makes it easier to communicate through time. A harder protocol reduces the noise of time.

Love this, yet after reflecting on the notion of “hardness” I would suggest that “promises” as described by Promise Theory (http://markburgess.org/promises.html) is a better descriptor. As he describes it:

“Promise Theory bridges the worlds of semantics and dynamics to describe interactions between autonomous agencies within a system. It provides a semi-formal language for modelling intent and its outcome, which results in a chemistry for cooperative behaviour.”

Money, law and government all depend on the efficacy of promises, and Burgess’ treatment of this topic is one I and many others have found fruitful in many domains.