Part 1/7 of the On Lore series.

In the last couple of years, I’ve become aware of some genuinely fresh management thinking from an emerging cohort of thinkers on the margins of the landscape of traditional institutions. At this point, it’s coherent enough, and represents enough of a break from mainstream intellectual traditions, that I count it as a distinct school of management thinking. If there are some things for which I turn to say Harvard Business School or Silicon Valley for fodder, there are other issues (more and more every year) for which I turn to this new school of what I call lorecraft. Rather appropriately, lorecraft has emerged from the internet itself, rather than from a particular geography.

This school of thought will likely start taking over senior management and leadership cultures within a decade. Arguably, lorecraft is the first truly internet-native school of management and organizational thinking, though I’m sure it won’t be the last.

The common feature in the work of these emerging thinkers is the centrality of lore, as in folklore, the lore of a fictional extended universe, or more pertinently, the water-cooler lore of an organization, in the framing of the traditional concerns of management and organizational theory. Lore, you might say is the feedstock of both stories and world-building, but is neither. It is raw cultural phenomenology.

Lore is both at the heart of how these thinkers view the world of work and organizations, and the means by which they prefer to act upon it.

Let’s look at three examples of lorecraft. The examples are from the work of three emerging masters (lords and ladies? witches and wizards?) of lorecraft: Rafael Fernandez, Kei Kreutler, and John Palmer.

Rafa’s Community Operational Framework

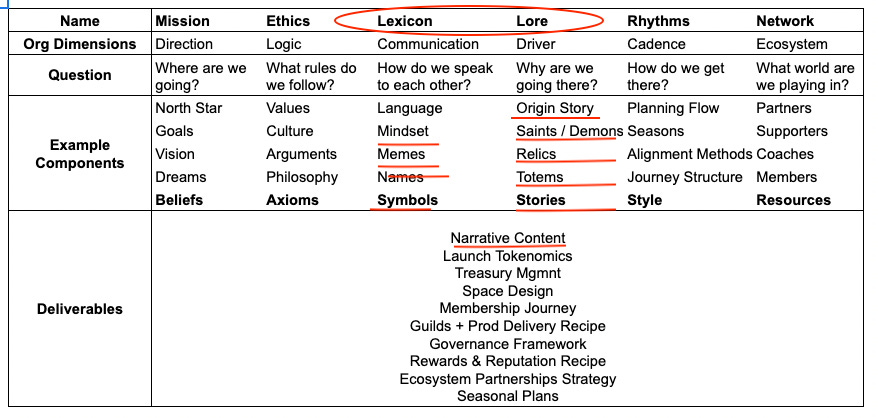

Rafa is developing an interesting set of ideas and mental models for working with DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations). Earlier this week, I randomly ended up using his Community Operational Framework with one of my own clients, with great success. Here is the framework in the form of a table, though it is just the tip of a much bigger iceberg he’s developing. The red annotations are mine.

What is notable about this construct is that while it inherits many elements from older traditions that will be familiar to older managers and leaders (even Boomers should be able to parse the Mission and Ethics columns), the core of it is the Lexicon and Lore columns, which have no real counterparts in older traditions. As far as I know, no MBA course covers lore and lexicon, and no airport business bestseller to date has unpacked those things.

In the two-day strategy meeting I was in, I introduced lore/lexicon as a lens for looking at the challenge we were working on, and I ended up getting tasked with actually instantiating that aspect of our discussions in the collective work output.

So I adopted Rafa’s table as a color-by-numbers cue, and improvised what I called a “memetic forecast” for the success scenario of the initiative we were discussing (ie, speculations about what sort of lore might emerge around the initiative if it succeeded).

It proved to be a highly fertile way of synthesizing the whole discussion.

In the process, I stumbled across a key insight that may or may not have been spotted before: lorecraft is the evil twin of marketing.

Specifically:

Marketing is the story insiders tell outsiders to influence them in some way

Lore is the story insiders tell themselves to manage their own psyches

This is a critical difference. Lore has a great deal of resemblance to, and overlap with, marketing, but is primarily a paradigm for managing the insides of an organization (to the extent there is an inside to such things as loose communities and ecosystems).

This means lore is a live modality even within nascent, early stage, and stealth efforts that have no marketing presence in an external context at all.

An implication that creates the sharp contrast to traditional marketing is that lore cannot be engineered in the same way marketing can be. While you can shape lore as it emerges, it is a matter of subtle gardening and curation. You do not go around trying to invent brand names, logos, and brand-identity postures for emerging lore. You are not pumping “messaging” into scarce “channels” pointed at distant “markets.” You act like a gardener trying to make your own garden thrive, cutting away unhealthy bits, and supporting the healthy bits.

This is why I ended up framing my contribution to the discussion a “memetic forecast” rather than a “marketing strategy.” Lore is something you witness, and attempt to shape as it emerges, if it emerges, not something you design and execute. You cannot, for instance, set out to write an origin myth. At least not one that will work as lore (though it may work as part of a grift). You can only recognize and institutionalize one.

A very early sign of this mindset was visible even 15 years ago, when early internet marketers made fun of traditional marketers for thinking that they could “make viral videos.” True virality, it is now obvious in hindsight, is an emergent feature of lore, not an engineered feature1 of marketing.

Lorecraft is a complex descendant of such internet-ancient insights into the nature of virality and memetic vigor. Now-classic principles like “provide the fuel, not the spark” led directly to contemporary lorecraft mental models like headless brands.

Today, lore is getting increasingly clearly separated from marketing. One sign is that while marketing must still attempt to distill and simplify ideas as much as possible to get through to distant fresh minds as quickly and efficiently as possible, lore is often perversely inaccessible, and the illegibility is often considered a feature rather than a bug.

Aspirants to insider status in a group must work to gain the subcultural literacy that allows them to access a body of lore. Lore can supply fuel for marketing, but cannot itself be marketed. At best, in rare cases, it can be taught.

Kei’s Eight Qualities of DAOs

The second example is this essay by Kei Kreutler, who heads up strategy at Gnosis, on the Eight Qualities of DAOs.

The piece references my gloss on Gareth Morgan’s classic Images of Organization, but beyond borrowing Morgan’s basic scheme of an inventory of eight gestalt qualities, it is largely an original mental model of organizations.

Kei’s eight qualities are: autopoietic, alegal, superscalable, executable, permissionless, aligned, co-owned, mnemonic. Her framework is something of a cross between an impenetrable edifice of German idealism and an ironic astrology.

It is a lore framework for mapping the contours of an organization rather than a template of design imperatives to act upon systematically (once again the lorecraft bias towards witnessing and shaping over designing and executing is apparent).

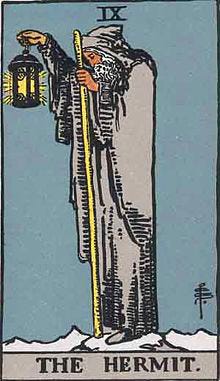

Kei’s essay is richly illustrated with evocative tarot-like cards like this one:

Since Kei, like many lorecraft thinkers and practitioners, came to strategy by way of art and design, it is tempting to focus on the textual arguments and dismiss the imagery as merely a personal conceit.

But the incorporation of such imagery is neither incidental, nor cosmetic.

Right-brained evocative imagery as a means of both communication and cognitive anchoring is as fundamental to lorecraft as constructs like 2x2s and block diagrams are to traditional management. As an aside, lorecraft tends to be much more conscious and ironically aware of its cognitive tooling than traditional management.

It is also tempting to dismiss this kind of thing as non-rigorous solipsism, but that would be a bad mistake. Lorecraft does rely on rigorous argumentation and empirical-phenomenological grounding. In fact it is much more grounded and empiricist than traditional management thinking, with its arsenal of unacknowledged myth-and-ceremony cognitive tooling that gestures at empirical rigor without actually embodying it.

But it could hardly be otherwise. Unlike traditional organizations, the prototypical objects of study for lorecraft are self-logging digital-native organizations that by their very nature tend to produce copious streams of data exhaust, and are generally equipped with sophisticated analytics tools that make ungrounded theaters of speculative managerialism2 that much harder.

I think of right-brained lorecraft tools as centering and cultivating rapid, intuitive decision-making behaviors over analysis-paralysis. So rigor and empiricism evolve in the background at their own pace, as information becomes available and is routinely digested. A robust System 1 that races ahead of a slow-and-steady System 2.3 By contrast, traditional management often tends to let a theater of rigor and empiricism, driven by a deep anxiety about uncertainty, lead pseudo-rigorous thinking over a cliff. Ineffective System 1 in the guise of insubstantial System 2.

Would you rather run blindly off a cliff, armed with a spreadsheet full of hard-earned but deeply flawed data, unaware that the cliff is even there, or thoughtfully navigate it with appropriately uncertainty-modulated mental models, with the unknown front-and-center in the form of a tarot card, and dashboards of live, accurate, but known-to-be-limited analytics off to one side?

While I haven’t yet deployed Kei’s eight qualities in a live-fire client interaction situation, I’ve been using it for offline brainstorming and analysis of problems I’m thinking about (I’ve learned the hard way that older managers are in general simply not ready for this kind of thing. Even where they appreciate the approach intellectual, the cognitive tooling it represents doesn’t quite compile in their work-brains).

John’s Lorecraft Aphorisms

While John Palmer does write interesting longer essays, it’s his tweets that repeatedly catch my eye. They are good examples of an emerging genre of aphorism that I think is central to the praxis of lorecraft.

Let me share two examples.

A current hot topic is whether or not particular organizations “qualify” as DAOs. Here’s John’s efficiently sardonic take:

I encountered this tweet just in time to avoid getting sucked down a bunnytrail of pointless pedantry on exactly this question, since I’m currently involved in explorations over at the Yak Collective on potentially uplifting ourselves to DAOhood. While DAOs and the novel blockchain tooling they rely on are real enough, current conversations have somehow gotten trapped within illusions of false precision.

Here’s one of his recent tweets that was an aha moment for me, crystallizing clearly the source of my discomfort with vibes:

I wrote about my own discomfort with vibes a few weeks ago:

A vibe is the feel of the least unsatisfying wrong resolution of a mystery

Or if you prefer pithy, vibe-y, aphoristic definitions, a vibe is an emotion pretending to be an explanation.

While my candidate aphorisms apply to the abuse of vibes as explanations, John’s tweet points to a more valuable general precautionary principle — vibes are often degenerate fogs of failed lorecraft clouding thought.

If your party or event boasts good vibes, that’s great. But if you expect a vibe to do the work of full-spectrum managerial lorecraft of the sort suggested by Rafa’s table or Kei’s eight qualities, your effort is doomed.

While management philosophizing by aphorism is not new, in the pre-Twitter era, aphorisms were delivered and received as lofty pronouncements with the the halo of divine commandments around them, and the force of Straussian authority — fat books or long speeches by old men with big titles — behind them.

Pre-Twitter aphorisms were aphorisms with halos4 so to speak. In lorecraft though, aphoristic pronouncements are not really about borrowed authority but about restoring balance to discourses that tend naturally vague due to the fundamental ambiguities of lore. In a world where most aphorisms are born in on the Hobbesian meme-battlefield of Twitter rather than in books or speeches by already-revered figures, aphorisms with halos are cringe anyway,5 but aphorisms without halos do actual work. They are tools of thought, not ornamentation.

Within lorecraft, the shrapnel of trenchant verbal pronouncements is a necessary ingredient because lorecraft is so much a matter of right-brained gestalts, intuitions, symbolism, and currents in the collective unconsciousness.

In other words, lorecraft doesn’t work without the kind of aphoristic sense-making John practices. It is not a nice-to-have poetic extra. It’s part of the working machinery of lorecraft.

Or perhaps you could say the only way to truly grok lore is to periodically lob a grenade into the fog of it.

Lorecraft is born baroque in a sense, ironically incorporating its own absurdities as load-bearing elements. Where industrial-era schools of management needed only the weak external force of satirical business cartoons to stabilize themselves, through some occasional puncturing of runaway self-regard, the fluid weirdness of lorecraft calls for stronger measures.

There can be no earnest way to do lorecraft because humor, satire, and irony are necessarily baked into the mode itself. It is like kayfabe in that way. But this does not mean lorecraft is unserious. Unlike kayfabe, the wrestling itself is real, even if the coins are memes.

A Millennial Management School

There are of course, other thinkers besides Rafa, Kei, and John in the lorecraft school of management. And the school of thought isn’t really limited to management — it seems to rather ambitiously take all of culture as its scope.

While these three are the ones whose work I’ve so far found myself drawing on and citing in my own consulting work, there are several others who belong in this emerging tradition.

The Other Internet crew (of which Kei and John are a part, and which includes Toby Shorin and Aaron Lewis who have both contributed posts to ribbonfarm) is a part of this, and is currently publishing a research series on lore called the Lore Zone. There are many others, building, writing, or investing in ways that seem rooted in lore.

I do have some speculations on why and how it emerged though.

Lorecraft is clearly a strikingly millennial school of management thinking. All the thinkers who belong in this tradition are, as far as I can tell, between about 28-35 or so. They are firmly middle-of-the-pack millennials. Founders of startups who seem to practice a sort of management by lorecraft, such as Conor White-Sullivan of Roam Research, are also in this cohort.

Unlike older millennials and GenXers like me, they joined the workforce late enough that their thinking was not too influenced (contaminated?) by the baggage of traditional industrial organizations. Unlike Zoomers, they already have experience of workplaces — but crucially workplaces that have already been transformed by the internet in a way that starkly reveals the inadequacy of existing management traditions. And also unlike Zoomers, they enjoyed at least a few years of Pax Neoliberalia before all hell broke loose in 2015, just as the Zoomers were starting to hit high school. They are aware that a better world is possible, even if the one that’s just collapsed is now past resurrection.

My first instinct, when I noticed this school of thought emerging a few years ago, was to disregard its peculiar tendencies as cosmetic artifacts of the gaming (both tabletop, such as MtG, and MMO) and extended-universe/world-building milieus this generation grew up in (think Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, MCU, vast anime franchises, and so on). After all, those domains are all about lore.

Then I noticed that the members of this school were disproportionately from the worlds of art, UX, and design, and I thought perhaps they were very naturally drawing on experiences with those things for their ideas about management and organization. After all, a UX is an embodied metaphor, and a sort of of little world of lore.

But neither of these explanations seemed entirely adequate. There are aspects of lorecraft that don’t really have a convenient prehistory or traceable origin myth in gaming or fiction, and elements of it that don’t obviously derive from design and UX.

Then it hit me: lorecraft is a natural and adaptive intellectual response to the automation of vast swathes of managerial/leadership functions, and organizational processes.

The only question is: is the adaptation a cope or a capability?

Cope or Capability?

When “HR” to you mainly means a bunch of cloud apps rather than Toby from The Office, when even your boss is potentially an app streaming tasks and bounties at you rather than a person, when your world of work does not exist in the reality distortion field of a Steve Jobs, but in the inanimate reality distortion field of a stack of cobbled together SaaS tools, you end up thinking very differently about traditional questions of supervision, authority, tasking, and coordination.

When you start earning a living in what seem like play money tokens that are mysteriously valuable enough to pay your bills with, you really start to take a hard look at what the so-called adults have been telling you, about how the world works.

This turn to lorecraft is in a way very counterintuitive, if we accept that it is an adaptation to automation. Shouldn’t an automated environment make you more robotic yourself? Not more immersed in fantastic imaginings?

But it makes sense if you think it through. You end up doing more of what the machines don’t. Where Organization Man types were forced to function as machines, workers entering the workforce today are forced to function in a vacuum of opportunities to act mechanically.

Both on-demand Web2 cloud infrastructure and Web3 decentralized protocol infrastructure automate vast amounts of hard-edged bureaucratic functions that were previously wrapped in multiple layers of human agency and affect. With Web3, this technological evolution is headed in the direction of complete automation at the core.

Instead of work as something you do for a maternalistic entity with a human face (sometimes nurturing, sometimes abusive) between you and every algorithmic process, you get a cloth mommy API if you’re lucky and a wire mommy API if you’re not.

This suggests a skeptical null hypothesis — lorecraft is perhaps a kind of self-soothing behavior in individuals caught up in a highly automated, non-nurturing, and inhuman work environment. Being raised by TV is a walk in the park compared to being raised by apps.

This is the hypothesis of lorecraft as a cope.

But there’s a really compelling alternate hypothesis — lorecraft is how you design and manage organizations where all the dull and boring stuff is increasingly being automated away, and what’s left of management and leadership functions is increasingly just the interesting and hard to automate stuff.

And the way you get good at it is by getting increasingly attuned to the softer, subtler side of organizations. To the extent these subtle and nebulous forces can be understood and manipulated with precision and deftness (soon with deep learning for leverage), you get vastly more sophisticated organizations.

Lorecraft is about acquiring that precision and deftness. About preparing to manage a future of machine learning rather than a past of paper forms.

This is the hypothesis of lorecraft as a genuinely new managerial capability.

I think this explanation is in fact the correct one. As we will see later in this series, while coping mechanisms play a major role in lore, lorecrafting itself is not a coping mechanism.

Though lorecraft is in its infancy right now as a serious management model, it is evolving rapidly in both power and conceptual sophistication. Many things older generations of managers learned in easy ways, this generation will learn in hard ways. Some of the time, translating older management ideas to lorecraft-native forms will be helpful. Other times, those ideas will prove to be baggage best discarded, either serving organizational functions that would be vestigial in an internet-native context, or better reinvented than ported.

A decade ago, lorecraft was largely limited to edgelords haunting online fora thinking up the next troll for lulz and electoral mayhem. Now lorecraft is being used to manage treasuries worth millions, launch complex commercial projects, and design automation deathstars for fun and profit. A lot can and will go wrong. There’s a lot more involved in launching space missions than in launching meme campaigns.

But not as much more as older people imagine. And Kerbal Space Program covers more of the gap than you might think.

If this hypothesis of lorecraft as an emerging managerial capability is correct, any organization — be it a traditional corporation, a DAO, or just a complex money-making coordination pattern passing through Twitter or TikTok like a wave — will thrive and do interesting things to the extent it has both interesting ideas and content — and skilled lorecraft at the helm.

Increasingly, lorecraft will run billion-dollar ventures (whether or not they’re organized as DAOs), wage war, and run political campaigns.

Lorecraft is already a significant presence in the latter two domains. Arguably lorecraft drove the outcomes of the last couple of US Presidential elections, and to a significant degree is shaping the course of the Russia-Ukraine war. While heavy artillery and Javelin missiles will shape the war in tangible ways, lorecraft operating on all sides has already trashed most expected scenarios and funneled events towards weird new regimes not seen before on CNN or Twitter.

Those expecting simple replays of either Russian or American misadventures in Afghanistan, Syria, Vietnam, or Iraq are, I think, going to be surprised by the new elements that might emerge here.

Prefigurings

I suppose one reason I’m interested in the lands of lorecraft, besides a basic pragmatic curiosity about ideas I might be able to use, is the uncomfortable sense that some of my own writing vaguely prefigured some of the ideas now emerging in fully realized forms. And I’m sure I’m not the only one my age who feels this way.

To whatever extent I have contributed to management thinking and practice so far, it has been in a mode that could be called late industrial. My own writing on management and business is, in hindsight, at least 50% a product of a late-industrial organizational and business context.

It is a context that breeds, and calls for, the posture of darkly amused cynicism that Gen X has famously, if not credibly, affected since the 80s. But unlike others of my generation with similar interests and aptitudes, thanks to being a blogger and a free-agent, I am also 50% a product of an early-internet context.

It is a two-faced Janus mode of being. Or if you prefer a less lore-y metaphor, a Prius-like hybrid mode of being, between the gasoline-fueled past and the battery-powered future.

I suppose every generation feels like it is experiencing a hybrid mode of being, but I think Gen X has a particularly solid case for claiming this particular kind of schizophrenia as its very own generational condition.

One Janus face has been turned, for fifteen years, towards the past, acutely alive to the enormous power and life left in the old institutions I grew middle-aged in, but darkly amused by the increasingly threadbare fictions that increasingly fail to sustain them. One half of my own best-known writing, comprising things like The Gervais Principle, Be Slightly Evil, Premium Mediocre, and The Internet of Beefs, clearly, and perhaps even stereotypically, draws from what this face has been witnessing and participating in.

The other Janus face has been turned, through the same 15 years, towards the future, gazing with non-native fascination at the alien forms of institutional life that are rapidly growing like weeds all around us. A new landscape I’ll never be more than a migrant in. The other half of my perhaps less-known writings, comprising things like Welcome to the Future Nauseous, A Brief History of the Corporation, Breaking Smart, The Design of Escaped Realities, Domestic Cozy, and Tempo, draws from what this face has been witnessing and participating in.

It would be fun to try and classify all my writing into these two categories. And I can think of other writers on management topics about my age whose work seems to factor out the same way.

I suppose I could claim, with some justice, that the future-positive half of my writing did in fact foreshadow some of the emerging thinking. But some part of me strongly resists identifying with lorecraft, despite the fact that the future clearly seems to belong to it.

I mean, this stuff is at some level ridiculous to my hidebound Gen X mind. Lore? Magic? Witchcraft? Vibes? Management by memes? Lexicons and larps? Tweeted incantations of power? Work as a multiplayer game? The workplace as an extended universe fiction?

Good for fun and games and actual fiction, but as a basis for Serious Things? Really?

When you’ve spent the first 45 years of your life convinced you are some sort of hard realist, with an imagination shaped by the end of the Cold War and the unforgiving economic landscapes of the early neoliberal world order, it is hard to entertain the thought that perhaps reality is, or could potentially transform into, some sort of malleable medium for imaginations addled by something uncomfortably close to magical thinking.

But of the two worlds I’ve been witnessing, I am becoming convinced that the emerging weird world being claimed by lorecraft, with tarot cards and literal magical thinking in the mix, is actually more real, and has been all along.

The dying world I spent so many years understanding on the other hand, despite the powerful normalcy field surrounding it, is in fact the less real world. The magical thinking that governs it is all the more powerful because those caught up in it are not even aware of it.

Next: Part 2/7 — Lore as Imaginative Irony.

At best you can A/B test your way to formulas that yield more virality than other formulas, but such frankenstein hybridization of lore and marketing reeks of gain-of-function experimentation in a dark adtech lab.

Unlike John Wanamaker, who famously declared that half of his advertising worked, he just didn’t know which half, digital-native organizations not only know, they automatically act on that knowledge. Lorecraft cannot unknow what organizational sousveillance makes known. It can only retreat to what the participatory panopticon cannot see.

The robustly useful System 1/System 2 distinction is one element of Kahnemannian lore that seems to have survived the depredations of the replication crisis in social psychology that has somewhat tarnished his Nobel medal.

Drucker, for example, is usually quoted with a kind of uncritical reverence in a spirit of borrowed authority. Even irony and satire in the pronouncements don’t change this. They merely serve as a kind of borrowed verbal sprezzatura to lend a tone ton opinion. Patton’s famous line, “No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for his country” is usually quoted the same way Drucker’s many aphorisms are. Salty borrowed authority is borrowed authority nevertheless.

I won’t name names, but you all know the people I’m thinking of here.

To stay in lorecraft terminology: this post is "magic" > thanks for this brainmelt, Venkat!

There is definitely a magic (or magick) revival going on in society.

For a very Venkat-like theory of what is happening with this, I recommend Lionel Snell, My Years of Magical Thinking.

https://www.amazon.com/Years-Magical-Thinking-Lionel-Snell-ebook/dp/B01NB0H2FZ/

The core belief of the old order was that there was an obvious objective world that could be manipulated by well-understood objective techniques.

The new belief is that subjectivity is central, and the challenge is to build shared subjectivities using well-understood but wooly techniques.

Both have always existed, but the former, as the only allowed business modality for the last several decades, has burned itself out by over-application.