This essay is part of the Protocol Narratives series

The hermetic proverb, as above, so below, is one of my sense-making lighthouses. Other things being equal, if the world is going nuts, your life will be going nuts too. If the world is sailing along beautifully, driven by serendipitous worldwinds, your life will sail along beautifully too.

This fractal nature of reality is obvious during periods of crisis (as above, so below is basically a tautology during times of war or natural disaster) but is much less obvious during normal times. During normal times, the effects of large forces acting on small realities are easy to misattribute to small forces. A personal example: I recently realized that a great many things I had been attributing to my personal choices and circumstances over the last decade were actually driven by zero-interest rate economic conditions.

Our language around the coupling between the large and small realities of our lives is very limited, but one useful word for talking about it is anomie. Anomie is an individual micro-response to macro-conditions being either too structured, or too unstructured. Humans do not thrive under either absolute chaos or absolute regimentation (whether it is benevolent or malevolent is a secondary consideration).

The idea of anomie gives us a useful way to assess the level of harmony between large and small realities. When there is just the right amount of structure, anomie tends to disappear. Any residual angst is your own problem.

What is this condition of harmony? I submit that this is the condition of strong narratability. In my July 21 issue on Unnarratability, I defined this as follows:

In [strongly narratable] conditions, the logic of a situation and the flow of events is clear to the point of being boring. Even extremely careless observers with no talent for coherent storytelling can provide a reasonable account of it.

Strong narratability has a particular effect on the as above, so below coupling between macro and micro. It allows us to correctly attribute certain features in our lives to broad macro circumstances, and other features to individual, micro circumstances.

One way to get there is, as I’ve said, through crisis. The naturally strong narratability of crisis situations explains why it is possible to feel strangely alive and motivated in terrible times. The times lend themselves to easy separate micro and macro. This is one reason politicians like to create crises and conjure up non-existent external threats — it creates narrative traction artificially.

But what about non-crisis times? How do you achieve such a separation?

Let’s say you’re feeling depressed. Are you perhaps responding, as a sensitive human should, to something like the steady stream of despair-inducing news about climate change? Or are you responding to stress at work or in a relationship? Or are you merely dehydrated?

These discriminations are not always trivial to make. It took me years to learn to tell apart certain gloomy moods from dehydration. It helps to know whether you should respond to a felt mood by changing careers, going on a restorative vacation, breaking up with a partner, or drinking a glass of water.

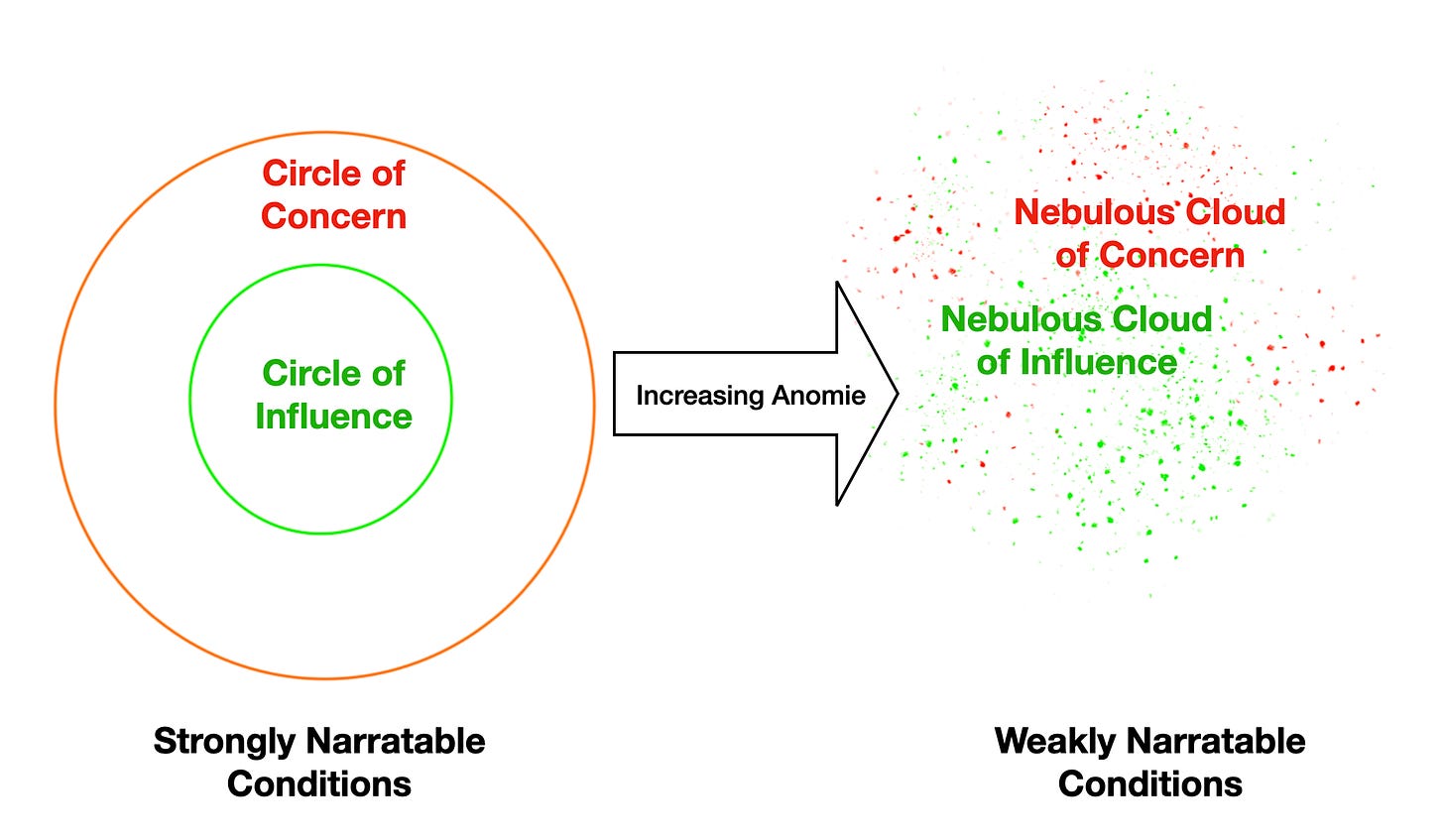

Strongly narratable conditions are psychologically valuable precisely because they allow you to make such separations efficiently. They allow you to draw what Stephen Covey called the circle of concern and circle of influence accurately. They are an answer to the serenity prayer —

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference

Since I wrote the previous essay, I have updated my mental models somewhat. Strong vs. weak narratability is partly a function of circumstances and the prevailing landscape of technological agency, but also partly a function of the sophistication of narrative technologies, by which I mean the templates and patterns used to tell stories (about both real and imagined events) in a given time and place.

In other words, strong/weak narratability is a function of narrative technology rather than an absolute condition. What’s unnarratable chaos to one narrative technology may be strongly narratable banality to another.

Narrative Technologies

This ability to catalyze an effective separation of concerns into micro (influenceable by the typical human) and macro (not influenceable by the typical human) is, I suspect, the primary practical affordance of narrative technologies. Powerful narrative technologies create strongly narratable conditions. In the picture below, what’s in the left hand side of the diagram versus right hand side is a function of the narrative technology.

To first order, and relative to a given narrative technology, narratability IS separability of concerns. It is simply harder to tell stories about nebulous clouds of concern and influence. You have to be a much better storyteller to do so. Any hack can tell a decent story under strongly narratable conditions. You’d have to be a Tolstoy or Dostoyevsky to tell a story under weakly narratable conditions (and those stories are going to be “great” relative to their narrative technology as a result — having to shoulder a much bigger burden of unnarratability). And sufficiently unnarratable conditions will defeat even the best storytellers within a narrative technology, leaving behind one sort of anomie or the other. At that point, only the rise of a new, superior narrative technology can conquer the conditions.

I’m using narrative technology rather than medium, because I don’t mean forms like novels, movies, or Presidential addresses. Nor do I mean a narrative model like the Hero’s Journey or competing constructs like Ursula Le Guin’s Carrier Bag theory.

By narrative technology, I mean a set of widely recognized and understood narrative conventions and techniques shaped by contemporary circumstances and shared assumptions about reality and technological agency, underwriting a particular kind of sense-making literacy.

For example, most modern genre romances are products of a single narrative technology, independent of the novels, movies, and television shows they might drive. If you possess the sense-making literacy to read a romance novel, you also possess the sense-making literacy to watch a romance movie.

But cowboy adventures and space operas are not part of the same narrative technology, even though both might loosely conform to the Hero’s Journey, and even share specific tropes like fast-draw gunslinging. They differ in the specific assumptions they make about reality and agency, follow different conventions, and require different sense-making literacies to parse.

To take a trivial example at the level of vocabulary, to parse the phrase, in a galaxy far far away, you need to know what a galaxy is. To take a more complex example at the level of visual concepts, a light-saber makes no sense to an audience not familiar with electricity or the idea of a laser. A medieval Star Wars viewer, assuming they could get past the shock of movie technology, might wonder why the trope of a flaming sword has been updated to a strange glowing stick that appears and disappears with the push of a button. But they would be able to make sense of Emperor Palpatine shooting lightning bolts out of his hands like a Greek god, because that visual concept only requires familiarity with lightning to parse, not electricity. It has been inherited from older narrative technologies.

The sense-making literacy associated with a narrative technology is closely related to basic linguistic literacy. This becomes particularly clear when science fiction is translated to languages that haven’t kept up with modern knowledge, and are mired in dated epistemologies. In the Hindi dubbed version of Jurrasic Park, for example, dinosaur was translated to big lizard, which is not exactly wrong, but isn’t quite right either.

Science fiction in general does not translate well to Hindi. The few original Hindi science-fiction movies that have been made have generally struggled with basic exposition. While even the poor in India today have access to sophisticated technologies like smartphones, and have a high degree of literacy in their use (far exceeding education levels), Indian vernacular narrative technologies struggle to talk about contemporary modernity. It is not just that the vocabulary is insufficient; the mental models and world-views are insufficient too. The Hindi commentary accompanying the recent launch of India’s Chandrayan 3 lunar mission was revealing: there is basically no easy way to talk about the intricacies of space missions in Hindi. Modernity is much more strongly narratable in English-based narrative technologies than in Hindi-based ones. This is one reason almost all higher education in India is in English. You can earn a degree in history or Sanskrit without knowing English, but not a degree in engineering or medicine. I would struggle to translate most of my writing to Hindi, even though I am fluent in the language, because the things I write about are basically unnarratable in ordinary Hindi.

But increasingly, all available narrative technologies, based in every language, are failing. The world is becoming unnarratable even to the most advanced narrative technologies, built atop the most technologically modern languages like English.

Relative Narratability

The key thing to note about narrative technologies is this: Due to different groundings in phenomenology, different events will be narratable vs. unnarratable relative to different narrative technologies.

Narrative technologies achieve useful separations of concerns because they encode coherent assumptions about the nature of reality and human agency relative to contemporary states of knowledge. So they are satisfying when used for sense-making contemporary realities and deciding what to do. Old theological narrative technologies, such as Biblical ones, are fundamentally unsatisfying for making sense of contemporary reality, which is one reason people are generally less religious today than a thousand years ago. What would Jesus do? might still be a helpful question for moral dilemmas, but What would Steve Jobs do? is probably a better question to ask about product management dilemmas. Despite the formal similarity between the two questions, they belong in entirely different sense-making literacies, corresponding to entirely different narrative technologies. The latter question can access a great variety of modern realities that are simply not comprehended in Bible-vintage narrative technologies. Asking WWJD in a product management meeting would likely result in unnarratable confusion. Asking WWSJD would likely lead to a strongly narratable discussion.

Theologies do not separate modern concerns effectively into those that can be influenced and those that cannot.

The value of effective separation goes far beyond merely helping us maintain sanity at an individual level. It is the primary enabler of social scaling. Stronger narratability leads to stronger separability of concerns, and more powerful social scaling.

The Industrial Age perfected a planet-scale narrative technology — relatively simplistic grand narratives rooted in a handful of techno-economic ideologies — through a century of strongly narratable conditions. In the last essay, I termed these platform narratives.

The world today is increasingly unnarratable, but only relative to platform narratives. To rediscover narratability in our environment, we have to develop a new narrative technology that is up to the task. In the last essay, I named a candidate: protocol narratives. How do those work?

I’ll get to that in the next essay.

This essay feels like an injection of sanity into my veins.

Exceptional, as always.