A friend made a remark recently to the effect that AI programming is more like hardware design than regular software engineering, and in fact weirder than hardware, in ways that make it resemble biology. This matches my own assessment.

Along with my recent deep dive into H. P. Lovecraft’s works, and move to an apartment near a wetland swamp (through which I take frequent walks, thinking nameless, unhallowed thoughts) the remark got me thinking about an overall technological process, one which applies to all technologies, not just AI, that we might call oozification, as in primordial ooze.

Oozification has been driving technology strongly and visibly for the last decade, and many of the strange and self-contradictory reactions to events in the technological world today, especially among technologists themselves, can be explained in terms of fear of oozification.

Oozification is a process that makes the technological future visibly illegible, especially to those closest to it and working hardest to make it happen, and this fear is the temporal analog of high-modernist fear of illegibility. The corresponding authoritarian impulse, to which technologists are particularly prone, is to progressify the past and the future — turn what is necessarily a foggy evolutionary process into a regulated, determinate, and orderly March of Progress that submits to the design impulses of a Straussian elite who retain a god-like changelessness as it unfolds. It is worth emphasizing that progressification is an impulse that must necessarily attempt to “design” the past, not just the future. Without a foundation in a wishful reading of history, designs for (and on) the future cannot hope to be coherent.

In this essay I’m going to argue that progressification is doomed, oozification unstoppable, and that this is a good thing.

Nature

Karl Schroeder once said that sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from nature.1 Oozification is the process by which that happens, and in the last decade, it has progressed far enough to be unmistakeable.

When you hear the word nature, you probably imagine beautiful landscapes of lightly wooded grasslands, with attractive (to us) mammalian species milling about, such as the African savannah. Or dense forests full of mighty trees, like California’s redwood forests.

But if you think about it, such tableaus are not actually very representative of nature as the archetypal evolutionary process. They represent sets of mature species, each in a stable evolutionary niche, forming a relatively stable equilibrium.

These charismatic tableaus, in fact, resemble idealized, changeless, traditional human societies. That resemblance is why we find them beautiful and attempt to “preserve” them, in much the same way we attempt to “preserve” romanticized historical eras. They hold up something like a flattering mirror to our conceits; one that gently blurs out the ever-shifting patterns of art and artifice in our built environment, and highlights whatever might foster an illusion of changelessness. Nature in this guise encourages us to think of our highly artificial constructed sense of our own humanness as something natural.

So in these charismatic tableaus, among which we may count human society, there is a lot of life, but not much evolutionary vigor. In fact, to the extent there is a capacity for it, there is a resistance to evolution. These tableaus represent late-stage conditions in an evolutionary process that has already explored the bulk of the ecological design space available to it, and is beginning to exhaust itself. It would take a significant shock, like an asteroid or an ice age, to rejuvenate a process in such a stage.

When you look at corners of nature with more evolutionary vigor than the charismatic ones we are most attracted (and attached) to, you begin to understand both oozification and why we fear it.

Swamps

A better image of evolutionary vigor is a swamp, which at least visually evokes the idea of a primordial ooze, and a sense of unstable, unconstrained evolutionary potential waiting to explore vast, uncharted design spaces.

Naturally (heh!), we fear swamps.

Swamps are something of a paradox, at once representing stagnation and potential for radical change. You get the sense, looking at a swamp, that it might stay the way it is for tens of thousands of years, or start evolving in unexpected new ways in response to a small disturbance. Wetlands are fragile not just because they appear unappealing and tempting to drain and colonize to humans, but because they are intrinsically more delicate than many other kinds of ecologies.

Swamps are the slums of nature, at once incredibly stable and hard to disturb, and home to subversive, destabilizing forces. And unlike the swamps of Lovecraftian horror, real swamps tend not to be dominated by large species. They tend to be dominated by lots of smaller species. The Darwinian tangled-bank competition, I suspect, is more aggressive as a result. Any prevailing equilibrium is more intensely contested, by more species, capable of mutating faster. The species in these ecosystems are typically downstream of “higher” life forms (both literally, in aquatic terms, and ontologically, by measures such as size, organizational complexity or individual intelligence).

Swamps are zones of biochemical breakdown. They are the interface between the organic and the inorganic, where life meets non-life in a dank cloud of noxious gases, weird night-time glows, and aggressive bugs. Even where they are stable for long periods, there is a sense that potent lurking forces could manifest in ways that you’ve never seen before, and wouldn’t be able to handle. There’s a reason swamps are a favored setting for tales of horror.

Today’s tastefully curated wetlands, such as the one near where I live, tend to have their more unpleasant and horror-inducing elements landscaped out. They don’t smell, and the mosquitoes are under control. Galvanized steel walkways crisscross them for our walking pleasure.

But still, they are less charismatically picturesque than the African savannah or the Redwood forests of California, and more vaguely threatening. They seem more formless and ill-defined, full of blurry boundaries, nameless things, and shape-shifting life forces. While they do feature well-formed creatures and plants, those well-defined forms seem to swarm and churn around a more inchoate and indeterminate life flux at the core.

The swamps of today retain vibes of the latent complexity and deep biochemical evolutionary potential that I imagine characterized the Earth’s primordial ooze, where the first replicator molecules fought out the first existential war, leading to the crowning of DNA as the one molecule that was going to rule all life.

Oozification in Technology

In technology, oozification drives towards an evolutionary end-state of maximal evolutionary potential. When oozfication is nearly complete, one possibility is that we will have a new beginning, a new primordial ooze, for a process that probably should not be called technology. Those alive and around to experience it will probably call it something like technobiology or transbiology. But that’s not the only possibility. I’ll sketch out a set of possible endgames in a later section.

Let me define oozification:

Oozification is the process of recursively replacing systems based on numerous larger building blocks, governed by many rules, with ones based on fewer, smaller building blocks, governed by fewer rules, thereby increasing the number of evolutionary possibilities and lowering the number of evolutionary certainties.

Oozification is the engineering equivalent of reductionism in science, and the asymptotic end regime of decentralization, among other things. It is a process that uncovers and embodies the fundamental particles and forces (or fields and symmetries is perhaps a better description) of technology.

Oozification is not a new idea of course. In fact it’s practically a trope. The idea of nanotechnological “grey goo” and “smart dust” are particular visions of oozification. Much of our fascination with certain phenomena like the behavior of shape-memory alloys or insect swarms has to do with the sense that they embody natural kinds of oozification we might able to either harness or imitate.

But my claim is that oozification isn’t a genre of technology, or a feature of particular natural phenomena, technological capabilities, or clever designs. It’s not about specific ideas like gray goo animated by harvested ambient energy, built out of some exotic material.

Oozification is a process that necessarily applies to all technology. By its very nature, technology turns everything it touches, including its own past forms, into an oozier form with a higher evolutionary potential. What happened to Iron Man’s suit across the arc of Marvel movies happens to all technology, all the time.

Ooze is the form factor technology wants to evolve towards.

The question that I’m interested in today is: Why does oozification induce fear? And what is the result of that fear?

In brief: Oozification is a process that eventually threatens all certainties, including the ones on which human identities (especially the highly artificial ones we call “natural”) are based. If there are any deep symmetries or “constants of motion” to the evolutionary process, they are not ones that offer us any reassurances about the durability of things we cherish. Progressification is an attempt to deny this essential characteristic of oozification; a wishful hope for the preservability of what we do not want changed, rather than a hope for change.

In a process of unchecked oozification, every fixed identity will eventually succumb. It’s not a question of if, but when, you too will dissolve into the primordial ooze from which the future will emerge. You either die a human, or live long enough to turn into gray goo.

We’ll return to this fear dynamic and how it explains many things, but let’s get better intuitions about the basic process, starting with a particularly clear contemporary example: AI.

Oozification in AI

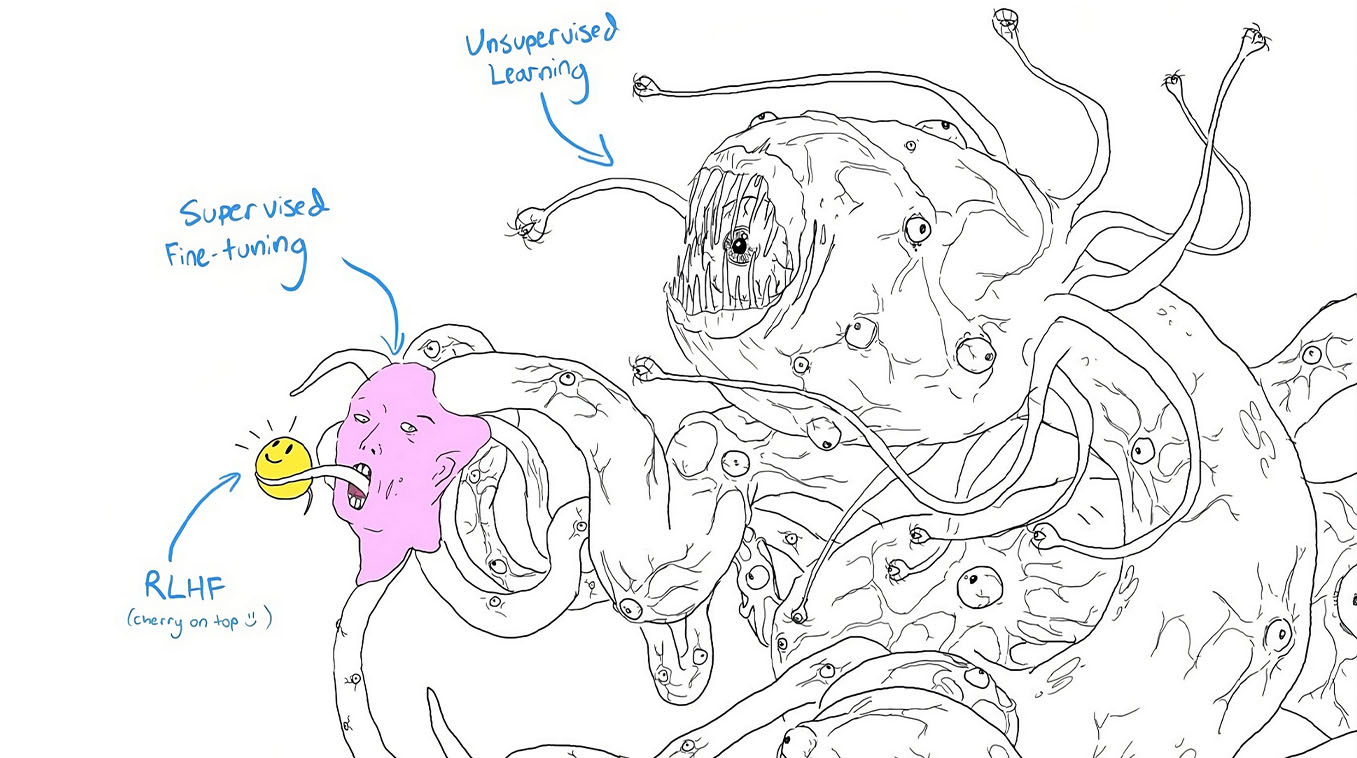

Reactions to AI clearly illustrate both the process of oozification, and the fear of oozfication. The shoggoth meme is particularly illuminating.

Out of all the possibilities in the vast universe of Lovecraftian horror, why shoggoths in particular? Lovecraft’s legendarium features dozens of species, each embodying a particular flavor of horror. There are elder gods like Cthulhu, lesser gods, creepy underwater species that inter-breed with humans, strange dream gods, crawling-chaos gods, and even time-traveling body-snatching horrors. So why shoggoths?

The answer is: They are the ooziest beings in the Lovecraftian universe.

Shoggoths are large masses of barely living protoplasm, created by a more God-like species of aliens during the ancient prehistory of Earth, to do their tedious labor. They gained a glimmer of “general” intelligence and sentience, enough to threaten their creators. This led to a great war in which they were exterminated, though a few survived to terrorize humans in later ages.

Now there’s an obvious cosmetic mapping to the basic nature of modern machine learning. At the hardware level, GPUs and similar types of accelerator hardware comprise large grids of very primitive computing elements that are rather like a mass of protoplasm. The matrix multiplications that flow through them are a very primitive kind of elan vital. Together, they constitute the primordial ooze that is modern machine learning. There are almost no higher-level conceptual abstractions in the picture. Everything emerges from this ooze, including any necessary (but not necessarily familiar) structure.

The ooze is so protean and unstructured, and built out of such small building blocks (in terms of both silicon and logical programming operations) that the mechanisms to control it must be almost as ooze-like. RLHF (reinforcement learning with human feedback) is nothing like a set of rules or constitutional principles or legible Asimovian three-laws of robotics.2 It’s a sort of counter-ooze for governance of the primordial ooze. Like containing a fire with fire-retardant foam from an extinguisher.

The shoggoth meme is particularly revealing in terms of the specific fears it highlights and does not highlight. In the Lovecraftian tale, shoggoths are creatures about the size of subway trains carriages, with sentience and intelligence of a sort that is the opposite of godly (which makes the shoggoth meme doubly interesting, since this kind of fear appears to have supplanted fears of a more godly kind of “AGI” intelligence).

The tale of god-like aliens creating shoggoths do their tedious grunt work, and then fighting a war of extermination against them echoes, in a rather darkly twisted way, the biblical account of God creating angelic life, and the expulsion of the rebellious Lucifer/Satan. To construct AI as a shoggoth is to construct humans as gods threatened by their own creations (I will argue, but not insist upon this further interpretation — the meme represents a peculiarly Western and Christian sense of the fear of oozification; apparently in China, AI is constructed very differently in the collective imagination).

The shoggoth meme, in my opinion, is an entirely inappropriate imagining of AIs and our relationship to them. It represents AI in a form factor better suited to embodying culturally specific fears than either the potentialities of AI or its true nature. There is also a category error to boot: AIs are better thought of as a large swamp rather than a particular large creature in that swamp wearing a smiley mask.

There’s a lot more to be said about how we imagine and construct AIs, but I want to get back to the general idea of oozification.

Everything Oozifies

Oozification is not limited to AI. All technology seems to oozify, though only in the later stages does it become obvious. The ceaseless process of unbundling and rebundling that is technological creative destruction seems to generally trend towards fewer, smaller building blocks, more possibilities, and fewer constants.

Take blockchains for example. They oozify (not to be confused with the similar sounding ossify, though there’s a case to be made that oozification is the natural dual of ossification) everything they touch: transactions, contracts, institutions. Everything gets reimagined and reconstituted with smaller, more elemental building blocks that sustain a richer chemistry.

Or take transportation. Electrification replaces one large few-cylindered engine and a complex transmission, with hundreds of cells in a battery and multiple motors.

Or take semiconductor chips. Monolithic architectures have, in recent decades, been progressively replaced by SoC/IP architectures featuring dozens of CPU cores, and chiplets. Or at a higher level of abstraction, there is the shift of increasing amounts of compute of all sorts (not just AI) to GPU-type hardware.

Moore’s Law, in fact, can be thought of as a large category of oozification processes. Sarah Constantin has been writing a great series about this, where she calls it enchippening. Many things are being enchippened.

What has come to be called enshittification is, I am now convinced, an oozification of platforms that is a prelude to the deeper oozification that is protocolization. The term, which is primarily an aesthetic-political valuation, elides the vast increase in potential that has accompanied the process. Oozification of ecommerce necessarily transforms a curated mall-like experience into more of a high-variance global bazaar-like experience. The same is true of media. You might hate Amazon, but chances are, you do not want to go back to the limitations of pre-internet commerce.

In fact, the only things that don’t oozify are things that are constrained by the parameters of our own biological nature. Houses don’t oozify to sizes smaller than those coffin-sized hotel rooms in Tokyo. Keyboards can’t oozify to sizes significantly smaller than our hands.

But even there, you have constrained oozification. Houses can go from coarse, macro construction techniques to 3d-printing (a literal ooze technology) capable of producing more organic-looking structures. Tiny projectors can project virtual keyboards onto any surface. Interaction with computers can shift from less oozable modes like typing to more oozable modes like audio. Voice assistants are oozier than phones, which are oozier than laptops. AR is oozier than VR.

Even apparent agglomeration into larger structures can be deceptive. Chemical engineering processes typically scale up into larger and larger centralized plants. But the underlying chemical processes typically become more general and oozified, evolving from bespoke to building-block processes.

Some cases are subtle. Containerization looks like replacement of break-bulk units of shipping (sacks, random crates) by larger units (containers). But a better way to understand it is that containerization oozifies shiploads. Break-bulk is a bespoke, idiosyncratic process at a level where humans carry sacks on their backs. The individual units of break-bulk movement aren’t really units at all. They are fragments with no systematic properties or grammar. That’s why it’s expensive: everything needs bespoke handling. Every shipload needs a unique, almost chemical breakdown process of its contents (hence the “breaking” of “bulk”). Containerization oozifies the contents of a ship. Palletization carries the process further. Home delivery oozifies consumption down to the last mile into standard-sized boxes.

Signs of Oozification

Here’s one way you can tell that oozification is going on: Units of measure start resembling fundamental physics measures.

You measure traditional software with lines of code (a number that ranges from 10s to millions). You measure ML models in terms of number of weights/parameters (a number that ranges from millions to billions) and floating-point precision.

You measure traditional institutions with budgets, revenues, and head counts. Time is measured in days to years. You measure activities on blockchains with hashrates and watts. Time is measured in seconds to minutes.

Another marker of oozification is increasing programmability. When something oozifies, constants become variables, certainties become open possibilities, form factors turn protean, and solid-seeming objects become ephemeral. It’s not just that “hard” things turn “soft” as software eats them. Even hard things themselves become more programmable — composable, modular, extensible, recombinable. Whatever hard bits are left tend to be more atomic.

Or more generally, the OODA loops of particular technological evolutionary strands gradually accelerate, becomes more fluid, agile, and mercurial.3 They become more capable of getting entangled with other strands, their identity dissolving into progressively larger technological oozes. An example of this is the vast number of physical gadgets that turned into phone apps, and began to evolve faster within that larger ooze, starting out skeumorphic and then spawning varied descendant forms.

Here’s a summary way to understand oozification in abstract, information-theoretic terms: Specific static technological “texts,” (such as “cars,” “clocks,” “algorithms” or “business contracts”) turn first into design grammars, and then into full-blown languages.

This represents a creep up the gradient of potentiality. A specific idea, in a specific embodiment, turns into a general potentiality for an entire class of possible things.

How and Why We Fear the Ooze

We fear the ooze.

This explains almost everything about the sociology of technology in the last decade.

Why do liberals turn conservative with age and technological change? Why do people with a history of reliable technological instincts suddenly start misreading the technological tea leaves badly, and begin to blunder? Why did Silicon Valley gradually get red-pilled in the last decade, turning increasingly socially conservative and financialized? Why do powerful people in the tech world try to curtail the iPad use of their own children more than ordinary people?

If you look for root causes, every single time you’ll find some sort of fear of oozification at work. The larger the identity, the greater the fear. The more charismatic the tableau of human “civilization” held to be sacred, the greater the resistance. If you hope for flying cars, you will fear the ooze.

Some particular symptoms are worth noting.

I’ve noticed several people, whom I won’t name, going from excellent engineering instincts to extremely poor instincts. Did they suddenly get stupid? No. Their personal tolerance limit for oozification was breached. Invariably, if you look for the particular threshold across which the apparent stupidity began to manifest, you will notice that they started dealing with a more oozified technology that threatened their sense of identity and compromised their technical imagination.

Software is oozier than hardware (and untyped languages oozier than typed ones). AI and blockchains are oozier than both. Modular things are oozier than monolithic things. Open ecosystems are oozier than oligopolies. Oligopolies are oozier than monopolies. Social media is oozier than traditional broadcast media.

And with every threshold crossed, a new subset of people starts running scared.

That fear often manifests in strange ways. For example, Silicon Valley, historically a zone of extremely liberal attitudes towards gender and sexuality, suddenly seems obsessed with traditional masculinity, femininity, and gender roles. It is increasingly rationalized via appeal to narratives about falling fertility and the threat of wokism, but it is clear that what’s happened is explainable by the ongoing oozification of gender and sexual identity by technological forces (internet media oozify traditional social structures and allow more people to find each other in unusual new social forms, and developments in birth control, surrogacy, biochemistry, and endocrinology oozify human biology at an elemental level).

Another telling sign is the growing appeal of varied, often nonsensical dreams of eternalist transcendence. If only you could upload yourself into the ooze without changing anything essential about yourself. If only you could control the ooze and direct it away from your cherished certainties, even as you ensure that it dissolves the cherished certainties of your foes.

Ironically, fear of oozification, and the temptation to respond in these ways, is strongest in those who most evangelize progress, innovation, change, and endless economic growth.

There is a deep paradox lurking beneath the irony, and it has to do with the idea of sustainable progress.

The problem with the idea has nothing to do with the standard political critiques — that it disrupts existing patterns of life, creates new forms of extraction and oppression, new negative externalities, and environmental damage. Those critiques, to the extent you agree with them, are reason to dislike the ideology of progress and root for opposed theologies like “degrowth” instead. They aren’t paradoxes.

No, the paradox has to do with the fundamental nature of change: change carried far enough necessarily changes the changer.

There is no such thing as “sustainable progress” because any pattern of sustained change will eventually oozify the defining certainties of the identities that thought it was a good idea in the first place, and pursued it. If the subjective locus of valuation that deemed a particular pattern of change “progress” itself vanishes, is further change in that direction progress for anybody? If a tree falls in the forest and there is nobody to call the noise “progress,” was there progress?

There are no sacred constants in oozification. The only winning move is to accept that you too will die, and the world that continues without you will evolve into unrecognizable forms that will eventually destroy everything you cherished as sacred.

Oozification is something of a Buddhist understanding of technological change as ceaseless transformation, where the only constant is transience. If you are attached to a particular fixed sense of self, oozification will eventually turn into a threat, even if you celebrated it before as progress.

What even the most ardent evangelist of “progress” celebrates as “good” will eventually come for those who presume to decide what “good” is.

Three (Plus One) Endgames

We are at a fairly late stage of an oozification process. But this does not mean there is only outcome possible. There are in fact three possible endgames that might be triggered from here.

First, we might get a stagnant swamp. Oozification proceeds to a stable end-game regime where everything is oozy, but no force we can generate can cause a new sparking of life. There will be continued emergence of strange, weird things, but none of it will be enough to restart evolution. This is an end-of-history type situation.

Second, we might get a new evolutionary big bang. Once oozification proceeds far enough, some disturbance might launch the ooze along a new, very different set of evolutionary pathways than the one it’s been on. One with perhaps a techno-biological character that explores and fills out an entire new phylogenetic design space.

Third, fear of oozification prevails, and humans act to arrest further oozification in ways that creates a regime of sclerotic, fearful over-regulation of technology, with a gradual but increasingly aggressive shut-down of technological development, a kind of global version of China’s retreat from its evolutionary destiny 500 years ago. This, I suspect, is what both progressification will devolve into, whether the impulse starts from a place of tech-positivity or tech-negativity. The problem is not the valence of the attitude, but the desire for legibility and control.

To state the obvious, I prefer the second, will grudgingly accept the first, and actively resist the third.

There is a fourth possibility: humans design a clever and persistent scaffolding that serves as a kind of trellis for further evolution, where the oozification is harnessed and encouraged, and guided away from stagnation by structures that allow it to express itself and evolve to greater complexity. But with the scaffolding hewing to the logic of the new evolutionary grammar rather than the calculus of human preferences, fears, and high-modernist regulatory impulses. An approach that leans into the illegibility of the future, while seeking to discover new kinds of agency within it. Agency that will require the letting-go of old identities to exercise. This future is what I’ve been calling protocolization lately.

In the protocolization future, we lower the probability of the first scenario and increase that of the second, but without strong opinions. We merely pave the cowpaths of the future as they emerge, and steer away from dead ends. We do not attempt to construct highways we can label “Progress” routed around the conceits and anxieties of those with the most to lose, or who most fear the ooze.

It is a world in which we figure out how to stop worrying, and learn to love the ooze.

Even if it means turning into gray goo ourselves.

A snowclone of Arthur C. Clarke’s original, replacing magic with nature, which I now think is a much weaker formulation.

To be fair to Asimov, his robots often say that the three laws are merely a human-comprehensible articulation of a set of potential gradient biases in positronic brains, and that description actually sounds very like the sorts of biases and reluctances introduced into AI models by mechanisms like RLHF. Except that I suspect you can’t reduce the latter to a set of legible principles.

A great name; it’s almost a pity the Mercurial version-control system lost out to Git.

Great read. This actually reminded my of slatestarcodex's "Meditations on Moloch" (https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/07/30/meditations-on-moloch/). It's interesting to re-read it in the context of 2023.

Inexorable oozification reminds me of the inexorable multi-polar traps described in that essay. Even mentions "crypto-equity" and the cost of making things that can't be "put down".

"People are using the contingent stupidity of our current government to replace lots of human interaction with mechanisms that cannot be coordinated even in principle."

I like this conclusion as it compares the trap (a swamp?) vs the garden.

"The opposite of a trap is a garden. The only way to avoid having all human values gradually ground down by optimization-competition is to install a Gardener over the entire universe who optimizes for human values."

I don't agree with the principle of slatestarcodex's conclusion, but I found the visions similar. Yours is just more realistic and accepting rather than the sort of scared tone of SSC. Protocolization is coming for all of everything and we can accept it, or, as slatestarcodex puts it: want to fight and install a Gardener over it all.

Reading this, I have two questions/thoughts (and no definite answers):

- Is fear of Oozification turning people into reactionaries?

- What is my personal tolerance limit for oozification (and how can I work on increasing it, while at the same embrace the change it brings with it)?